Would a Tagged Hammerhead Shark Travel Widely”

from The Fishing Wire

Credit: Richard Herrmann/NOAA

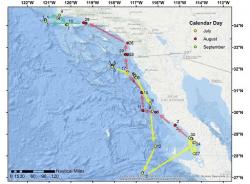

The first hammerhead shark fitted with a satellite tracking tag off Southern California has traveled more than 1,000 miles to Mexico and back again since NOAA Fisheries researchers tagged it near San Clemente Island about two months ago.

The shark, which is now off Ventura, California, is providing new insight into the great distance hammerheads may cover in search of food, mainly fish and squid. Unusually warm ocean temperatures in the Southern California Bight since last summer has drawn hammerheads north, making them more visible off Southern California.

“The surprising thing we’ve learned from this is just how much they move around within a season,” said Russ Vetter, Senior Scientist at NOAA Fisheries’ Southwest Fisheries Science Center in La Jolla, Calif. “This one went way down to central Baja and then shot back up here again just to find food, and that is a lot of territory for an animal to cover.”

Hammerheads have been sighted off Southern California more frequently in recent weeks, including one case last weekend where a hammerhead on a fishing line bit the foot of a kayaker reeling it in. While hammerheads are not usually aggressive, scientists warn that caution is warranted around sharks since they can act unpredictably.

Researchers on an annual NOAA shark survey caught the tagged female hammerhead June 30 off San Clemente Island and attached the satellite tag to its distinctive dorsal fin. The satellite position only, or SPOT, tag relays high resolution location data as the animal travels. The shark is known as a smooth hammerhead, one of three types of hammerheads that occur in California waters and also include bonnethead and scalloped hammerheads.

Researchers attached a satellite tag to a hammerhead shark captured in a regular offshore survey June 30. The tag should last two to three years.Credit: NOAA Fisheries/SWFSC

The smooth hammerhead shark traveled more than 1,000 miles to Mexico and back after it was tagged near San Clemente Island June 30.

Credit: NOAA Fisheries/SWFSC

The tagged shark measured more than seven feet long from its head to the fork of its tail. NOAA Fisheries scientists tagged a smooth hammerhead in the same area in 2008 with a different kind of tag that stores data for a few months and then detaches from the animal.

The shark tagging was conducted in collaboration with the Tagging of Pelagic Predators program.

Hammerhead habits are poorly known and researchers took advantage of the animal’s catch to learn more about its movements ahead of an approaching El Niño climate pattern, which typically boosts water temperatures along the West Coast. Patches of unusually warm water known collectively as “the warm blob” had raised temperatures off Southern California last year prior to El Niño, initially attracting warmer water species such as hammerheads.

The new satellite tag shows that the hammerhead swam more than 400 miles south after its capture to an area off the central Baja Peninsula known for its production of sardines and anchovy, Vetter said. The shark then returned north to an area off Ventura this week.The sharks’ distinctive hammer-shaped heads carry special sensory features and widely spaced eyes that may help them see and detect prey. The tagged hammerhead mostly hugged the continental shelf along the Pacific Coast but in one case made an open-ocean foray of a few hundred miles off of the Baja Peninsula. Vetter hopes the satellite tag will remain active for two to three years, providing a long-term record of the shark’s movements.

“It’s very interesting to us to see the neighborhoods this shark frequents,” he said. “For an animal to swim all the way to Baja just to see if there’s food suggests its food supply is not super abundant, which tells us something about conditions out there.”

The opportunity to track the shark during a warm El Niño year may provide clues about how hammerhead habitats may shift during gradual warming expected with climate change.

“It’s certainly possible they may spend more time farther north,” Vetter said. “We’ll be very curious to watch how far north this shark goes, which could give us an idea what to expect in the future.”