Catching Fishermen’s Attention with Barbless Circle Hooks

By Joseph Bennington-castro | NOAA Fisheries

from The Fishing Wire

In the summer of 2007, a Hawaiian monk seal got caught on a fishing hook off the coast of the Big Island of Hawai’i.

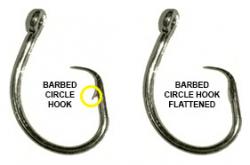

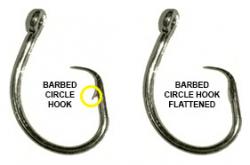

Barbed and barbless hooks

A barbed circle hook converted to a barbless circle hook using a crimping tool to flatten the hook’s barb.

The NOAA Fisheries Big Island monk seal response coordinator and his volunteers rushed out to aid the unfortunate animal, hoping to capture it and carefully remove the hook before the fishing gear could cause any serious damage. But before the volunteers could become rescuers, the monk seal shook its head, easily dislodging the hook in the process.

Was this, somehow, a defective hook?

No. It was a barbless circle hook, or a circle hook whose barb had been forcibly pressed down to reduce the severity of post-hooking injuries to endangered or protected species — such as Hawaiian monk seals and green sea turtles — that are accidentally hooked, and allow them to self-shed the hooks or be de-hooked easier.

This fateful event was a kind of vindication for the then-nascent NOAA Fisheries Barbless Circle Hook Project, which seeks to increase the awareness and use of barbless circle hooks among Hawai’i’s shoreline fishermen. Until this point, many NOAA researchers and fishermen alike questioned whether barbless hooks could really make any difference to protected species and fish that were accidentally hooked, says project manager Kurt Kawamoto, a direct yet welcoming man who tends to express his thoughts succinctly.

Though it seemed that the hooks would work in theory, “everybody was left hanging until that happened,” Kawamoto says. “And then it was like, ‘Okay, here it is. Here’s the proof.'”

The beginning

Aside from managing the Barbless Circle Hook Project, Kawamoto is a fisheries biologist for the NOAA Pacific Islands Fisheries Science Center (PIFSC). “My real job is fisheries monitoring,” says Kawamoto, who holds an undergraduate degree in zoology from the University of Hawai’i.

In this position, he manages the logbooks that fishermen must fill out while working in federal fisheries. These logbooks contain information on everything from the species of fish caught, to the fishing methods used, to the protected species disturbed during fishing practices. This data is available to PIFSC scientists who are conducting research on stock assessments and other things — the information is then used in fisheries-management decisions.

Barbless Circle Hook Project

Left to right: NOAA Fisheries’ Kimberly Maison, Mike Lamier and Kurt Kawamoto, along with DLNR’s Earl Miyamoto in front of the Barbless Circle Hook Project booth at a Lāna’i fishing tournament in 2009. Credit: NOAA Fisheries.

Before joining NOAA Fisheries 28 years ago, Kawamoto was a commercial fisherman himself. “I’m still a commercial fisherman,” he says. “But commercial fishing is very difficult and dangerous, and it’s hard to do when you get older.”

It was his background as a fisherman that may have ultimately allowed Kawamoto to develop the Barbless Circle Hook Project.

After a fisherman accidentally hooked a monk seal in the early 2000s, NOAA Fisheries held a meeting to discuss how to prevent this from happening again and help fishermen decrease their impact on protected species. Kawamoto was invited to this meeting because he’s a fisherman.

Before the meeting, switching to barbless circle hooks came to mind as a solution to the problem, Kawamoto says. “What else were we going to do? Shut down shoreline fishing?” Immediately after this meeting around 2005, he approached then-PIFSC director Sam Pooley with the idea of creating an outreach program to convince local fishermen to use these safer hooks, and sought financial support for at least 5 years.

“And he said, ‘OK.'” Kawamoto says. “That was it. And off I went.”

Getting off the ground

In Hawai’i, anglers predominately use circle hooks, particularly because they’re most suited for fishing the rugged near-shore areas around Hawai’i and for catch-and-release fishing, Kawamoto says.

Compared with the aptly named J-hooks, which can easily hook onto a fish’s innards and cause internal damage, circle hooks are self-setting and are designed to catch in the corner of the mouth as the fish swims away. What’s more, circle hooks are far less likely to get stuck on the bountiful reef and rocks along Hawai’i’s shoreline.

Ulua on circle hook

Ulua caught by Stephen Kilkenny with a barbless circle hook. Credit: Austin Kilkenny

Barbless circle hooks, however, are not manufactured or sold in the islands, so fishermen who want to switch to these hooks need to make their own — an easy, free process that only requires smashing down the barb (located near the tip of the hook) with a bench crimper or pliers.

A preliminary study presented at a conference in 2006 — shortly after the barbless project kicked off — suggested there is no difference between the effectiveness of barbed and barbless circle hooks in catching and landing various types of fish in Hawai’i. And in that same year, a local fisherman named Randall Elarco Jr. caught a 117-pound ulua (giant trevally) using a barbless circle hook — then-Mayor Mufi Hanneman later presented Elarco with the first “100-pounder” NOAA Barbless Circle Hook award.

“Just before that I was thinking, ‘What’s a milestone for the project?'” Kawamoto recalls. “And I would say to myself, ‘A 100-pounder would be really nice.’ The shoreline guys always want to catch a 100-pounder because it’s the equivalent of a troller catching a 1,000-pound marlin.”

Still, getting people to use the barbless circle hooks was an uphill battle from the get-go. Changing a person’s habits and perceptions is no simple matter, especially when that change appears risky. Fishing is the livelihood for many anglers, so the prospect of using a modified hook and not catching anything with it scares them, Kawamoto says.

Kawamoto, however, was up to the task, using a common-sense, honest approach to help win people over.

When he first started the project, Kawamoto made sure to exclusively use barbless circle hooks when he fished, allowing him to communicate his own experiences to fishermen. “It was very important to me, personally, to lead by example and to know what the fisherman might expect,” he says, adding that honesty and integrity were vital for getting fishermen’s cooperation. “Without that trust, I would have had nothing but words and theories.”

“He is so well known and respected by the fishermen,” says Earl Miyamoto, coordinator of the Marine Wildlife Program of the State of Hawai’i’s Department of Land and Natural Resources, who has successfully partnered with Kawamoto on the barbless project for nine years, helping to expand the crucial outreach efforts. “He would be a hard person to replace.”

And when clout and common sense isn’t enough, Kawamoto has persistence. In one early case, he spent four years trying to convince a fisherman to try out a barbless circle hook — he finally succeeded by jokingly questioning the fisherman’s courage.

“If I were to put my finger on it, I would say it’s the way he engages with people that convinces them,” Miyamoto says. “I think its Kurt’s directness and forwardness, and how he jokes a lot. He can come off as being serious, but he laughs a lot.”

Ever the modest person, Kawamoto stresses that “open-minded fishermen,” who are often part of the older generation of fishermen, also deserve credit for enacting change in the community. These people, he says, adopted the barbless circle hooks early on and even took to mentoring younger anglers.

“It’s not just me,” Kawamoto says. “I want to thank all of the anglers out there who have tried these hooks.”

Convincing the masses

To increase fishermen’s awareness of barbless circle hooks, Kawamoto is involved in various outreach activities. Grassroots help from many clubs, organizations, and individuals, including PIFSC volunteers, keep the project moving forward and enable the common-sense message to be integrated into public awareness.

For instance, Kawamoto and his collaborators attend events at numerous adult and keiki weekend fishing tournaments across the islands each year, and also work closely with the fishing clubs that often organize these tournaments.

“But we don’t go any place where we aren’t invited,” Kawamoto stresses. “Because you don’t want to go there and push your way in — that’s the quickest way to turn people off.”

Giving up weekends for these tournaments speaks volumes to the fisherman, Miyamoto says, adding that Kawamoto makes sure to come in “very local style,” arriving early and staying late to help setup and dismantle the tournament equipment. “It’s that approach and demeanor that’s contributed a lot of the success of the project,” he says.

100 Pound Ulua

Stephen Kilkenny with a 102.3 pound ulua, which he caught using a barbless circle hook in 2015. This catch is the third 100-pounder for the Barbless Circle Hook Project. Credit: Austin Kilkenny

Of course, the fact that the barbless circle hooks actually work also helps — fishermen using the hooks sometimes sweep the tournaments, taking the 1st-, 2nd-, and 3rd-place prizes in the top money-winning categories, Kawamoto notes. Furthermore, two additional 100-pounders have been caught with the hooks since the first one in 2006.

Aside from attending fishing tournaments, Kawamoto and his volunteers frequently show up at different ocean and fishing expos when they can. At these outreach events and tournaments, they hand out free barbless circle hooks, about 20,000 to 25,000 each year, Kawamoto says.

Kawamoto and Miyamoto attend established keiki events, during which Miyamoto takes the lead in holding a “Make It and Take It” activity. Here, they teach keiki how to make their own small barbless hooks using just pliers, and also give them take-home kits, which include fishing start-up information, protected species information and regulations, and a sampling of barbless hooks.

“That’s how we’re going to change people’s minds — with the kids,” Kawamoto says, adding that the kits are just as much for the keiki as they are for the parents.

At their various engagements, Kawamoto and his collaborators teach people about the benefits of going barbless. Over the years, the focus of this message has shifted from protected species to fish.

“Although we did focus a lot on the protected species problem at the start, the bigger thing that we keep telling the fishermen — and this is true — is that they interact with so much more fish than protected species,” he says. “After all, we’re fishermen and we want to catch fish.”

Sometimes fish get away because the line breaks, but they still have the hook in their mouths. If this circle hook is barbless, however, the fish can get it out sooner, allowing it to get back to eating quicker, improving its chance of surviving and getting caught again another day.

Additionally, many anglers target certain fish and release unwanted species that are accidentally caught — the barbless hooks allow them to de-hook the fish easier, resulting in less personal frustration and injury to the animal.

Kawamoto estimates that only a small percentage of fishermen use barbless circle hooks all the time, and that the lowest usage rates are among the general fishing public, who are not part of fishing clubs and tournaments. Still, he’s optimistic that barbless circle hooks will catch on with time. “We have made a lot of strides in getting people to use it,” he says.

Miyamoto is also hopeful about the project, and believes Kawamoto’s courteous nature — particularly how he sends out “thank you” emails after each event — will get them far.

“I don’t know if we’d be where we are were it not for that and him,” Miyamoto says. “He’s so unique to the program. It’s not just a job for him.”