Check out the exciting reveal of the track taken by the second tagged striper in the ongoing Northeast Striped Bass Tag Study.

By Jim Hutchinson, Jr.

from The Fishing Wire

Mention Asbury Park to just about anyone and Bruce Springsteen is typically the response. However, for local surfcasters – perhaps even the late Clarence Clemons, who as legend has it, could often be found livelining eels along the Monmouth County rockpiles in the wee hours after a Stone Pony gig – this rock and roll Jersey Shore town may best be known for the celebrated runs of herring at Deal Lake on the northern border with Allenhurst, and the trophy bass it would attract.

The lake was open naturally to the sea until the early 1890s when a man-made channel (flume) was built to allow the ocean to continue its connection. Significant work has been done by state and federal agencies to keep the flume operational over the years; but for Peter Dello of nearby Ocean, NJ, keeping the flume clear of debris is more of a labor of love.

“I’ve got my own little Maxwell House coffee can, with a long stick so I don’t have to bend down to pick up the trash,” Dello told me by phone during a Thanksgiving stay in the hospital following emergency bypass surgery. Dello has been a fixture on the local beaches where he has surfed for the past 40 years, and just recently began surfcasting.

Last October 22 while doing his regular cleanup, Dello became the second northeast beachcomber to stumble upon a veritable needle in the haystack when he found the Wildlife Computers’ MiniPSAT device from the Northeast Striped Bass Study.

“I was cleaning the beach and picked up this thing. I knew it looked weird,” Dello told me while lying in his hospital bed where local surfers and surfcasters alike have been sending well wishes following his holiday scare and noticeably absent from those beaches where he’d rather be.

“I grew up there, we used to play around in the flume,” he said.The $5,000 satellite tag that washed up along that legendary striper hotspot at the Jersey Shore began its transmission on October 19 after popping free of the striper named Freedom; three days later, it was clanging around inside Dello’s coffee can. In early November, that tag was in the hands of researchers who’ve been diligently working to analyze millions of data points stored inside, telling the tale of a 42-inch striped bass caught and released from a Fin Chasers charter on May 21 in the lower Hudson River. Where she traveled in those 152 days, and how far she went, may surprise every striper fisherman and scientist along the entire Striper Coast, north, south, and east of Asbury Park.Suffice to say, this striper was born to run.

GREETINGS FROM THE HUDSON

The Northeast Striped Bass Study kicked off on May 21, 2019 when a team comprised of staff from The Fisherman, Navionics and Gray FishTag Research set upon New York Harbor to deploy a pair of satellite tags in post-spawn striped bass for a five-month study. The first large striper to get fixed with a satellite tag, aptly named Liberty, was caught aboard Rocket Charters out of New York City on the East River with Capt. Paul Risi. It was considered finding a “needle in a haystack” when the first tag washed up along the beach in Massachusetts back in the summer and was picked up by a woman walking the beach; check out the amazing results of that tag right here!

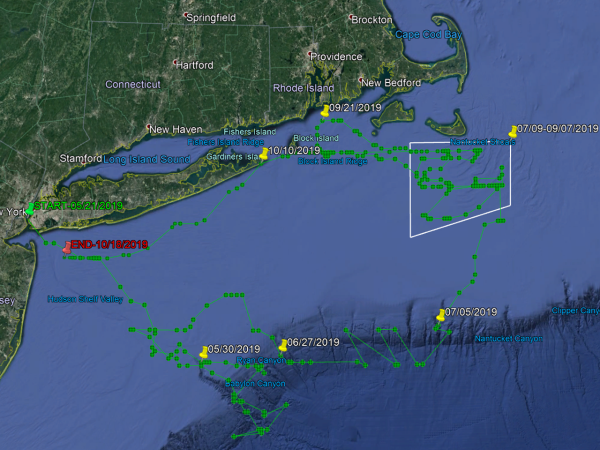

The second tagged fish, Freedom, was caught a little west of the first fish on May 21, not far from the Statue of Liberty aboard the charter boat Fin Chasers with captains Frank Wagenhoffer and Dave Rooney. The timing and location of the catch, tag and release project was planned around the end of the Hudson River spawning in hopes of capturing a pair of post-spawn bass; at 42 inches in length, Freedom was precisely the fish we were looking for!On December 5 at a conference at Gray FishTag Research in Florida, we learned the surprising truth behind Freedom. After being tagged in the lower Hudson River on May 21, data show Freedom heading in a southeast direction above the Hudson Shelf Valley, making it to the westernmost tip of the Hudson Canyon just inside the Babylon Valley – a distance of roughly 100 miles – for the Memorial Day weekend.

The information collected inside that Wildlife Computers MiniPAT tag reveals that Freedom spent the next month moving out and about within 20 or so nautical miles of that point, eventually zigzagging her way through Block Canyon out towards Veatch Canyon before heading north towards Nantucket Shoals in early July.

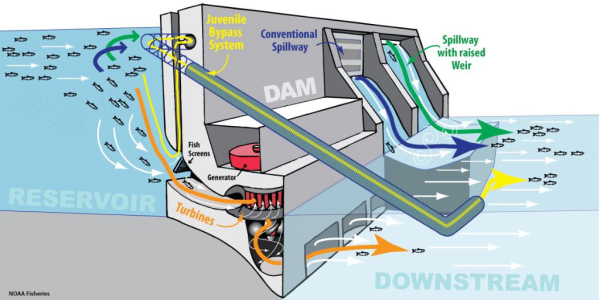

The beauty of these high-tech tags is that they incorporate light-based geolocation for tracking, time-at-depth histograms for measuring diving behavior, and a profile of depth and temperature. Some had questioned whether a larger predator like a white shark consumed the fish before making a beeline offshore; the data stored inside however show that both tagged fish were alive and swimming the entire time at sea.

NEW ENGLAND BOUND

Freedom spent the better part of July and all of August covering ground on the shoals outside of Massachusetts state waters, before heading northwest into Rhode Island Sound in what appears from the data points to be a somewhat circular pattern before cruising past Block Island to pay a visit to Montauk in early October.

For inshore fishermen and surfcasters in particular, Freedom didn’t make herself too available for capture for very long, ultimately sticking to the Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) for travel purposes, finally intersecting with her original May track out of the Hudson River in early October, before the tag disengaged pretty much on schedule east of Sandy Hook, NJ on Friday, October 18, just as the crew from The Fisherman was compiling our fishing reports for the November edition.

According to the tag data, a striped bass named “Freedom” spent much of her summer in the deep waters off Southern New England.

“Our predictions of a big bass attack this past week were right on the money,” reported North Jersey field editor JB Kasper that weekend. Sifting through our weekly reports at the time, it shows we had a pretty good nor’easter around that time, with a mid-week storm pushing wind and waves along the coast until that weekend. “When boats got back on the water on Saturday the 19th the stripers were still there and a flotilla of boats found mixed results,” Kasper noted in his New Jersey edition reports for the weekend, adding “Some of the best fishing was just inside the three mile line on Saturday.

”There’s no telling if Freedom made it past the “flotilla” of New York and New Jersey anglers on the grounds that week, but she did also have one of Gray’s green spaghetti tags affixed around her dorsal – as did Liberty – so there’s still a chance to learn more about both of these fish again in the future. One could roughly assume that Freedom enjoyed a bit of heavy feeding on bunker schools in the region before turning south along the three mile line with the rest of those big fish that anglers were finding off the Virginia coast as of early December. But as we’ve learned from the first two tags, our historic presumptions on striped bass migration might be off by as much as a few hundred miles.

According to the MiniPSAT data, Freedom spent much of the summer at depths of 50 to 75 feet, occasionally traveling to depths of between 150 and 200 feet.

“The science doesn’t always bear out the assumptions,” noted Dave Bulthuis, president of Pure Fishing’s North America division while sitting at the December 5 conference held by Gray FishTag in Lighthouse Point, FL. As one of the Advisory Board Members at Gray, Bulthuis and others spoke at length during the session about the need to provide better, more improved data for researchers managing coastal fisheries.

Dobbelaer stressed the ongoing goal “to get the data we desperately need,” while outlining for the group of advisors the urgency for better, more technologically advanced information. “This striped bass study reflects the movement of two fish caught and released in the Hudson River mouth and draws no conclusion of all striped bass behavior,” Dobbelaer said, adding “however, this groundbreaking movement lets us know that further work is a necessity from the team at Gray FishTag Research. There is so much more research that needs to be done to study the current patters and movements of striped bass.”In other words, if one is an anomaly, and two is a coincidence, it could take three or more high-tech satellite tags to help determine actual patterns.

CRITICAL BUY-IN

Another exciting bit of news learned at the Gray FishTag Research Advisory Board meeting in Florida on December 6 was that NOAA Fisheries is already actively engaged in the satellite tagging efforts. Eric Orbesen, Research Fishery Biologist with the fisheries agency and a specialist in highly migratory species and spatial movement is has worked with Gray FishTag Research professionals in ongoing swordfish research. Orbesen works out of NOAA’s Southeast Fisheries Science Center in Miami, but his ongoing participation in Gray tagging programs could be a good intro to other NOAA efforts with striped bass out of the Northeast Fisheries Science Center, which manages marine resources from the Gulf of Maine to Cape Hatteras.“Our goal is to continue to satellite tag many more striped bass in the Hudson River mouth during the same time of year in an effort to control the data collected on these great fish,” Dobbelaer told the folks assembled at the Florida conference. In fact, based on the early success of this groundbreaking work with striped bass, a new “spaghetti tag” project has also been launched with bull redfish in Northeast Florida where proceeds from the Full of Bull Tournament out of Jacksonville have been used to purchase 100 tag sticks and 1,000 streamer tags along with promotional materials as part of an education program there.

Closer to home for striper fishermen, funding efforts for new Wildlife Computers MiniPSAT devices for the ongoing Northeast Striped Bass Study have kicked into high gear. The 2019 study was funded by the charting professionals at Navionics, which has already signed on again for 2020. The Recreational Fishing Alliance (RFA) through its Fisheries Conservation Trust is also sponsoring a tag in 2020 utilizing monies raised through the annual Manhattan Cup catch and release striped bass tournament. Also kicking off during the holiday season was a new fundraising effort here at The Fisherman Magazine that seeks to find a core group of 1,000 individual investors to participate in the program.

For every $10 donation online, each “investor” will receive an exclusive Release, Reduce & Rebuild sticker to boast their participation in the tagging effort with their names added to an online list at TheFisherman.com. In just the first week of the fundraising, the effort raised $1,200 towards the purchase of additional Wildlife Computers MiniPSAT tags, which are valued at roughly $5,000 apiece. The initial promotional boost has also led to new pledges from within the recreational fishing community; looking ahead to the next round of tag deployments sometime this spring, it’s entirely possible that we have six or seven post-spawn stripers swimming around with pricey MiniPSAT devices next summer. |