Wisconsin stocked Chinook salmon outperform Lake Michigan average, new research shows

from The Fishing Wire

Today’s feature comes to us from the Wisconsin DNR, which is justifiably proud of the success of its Chinook salmon stocking program on Lake Michigan.

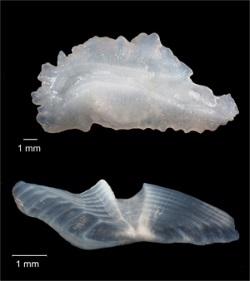

Wisconsin stocked chinook salmon outperform Lake Michigan average, new research shows A cooperative research project by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, DNR and agencies in other states used a mechanical process to insert tiny coded wire tags into the snouts of young lake trout and chinook. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service PhotoMADISON — Chinook salmon stocked by the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources survive very well and contribute substantially to the state’s strong Lake Michigan fishery, new research from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and DNR shows.

As the lake’s top predator, it’s common for both stocked and wild chinook to travel hundreds of miles to feed as they mature and at any given time during the summer, state anglers may catch chinook stocked by Wisconsin, Michigan, Illinois or Indiana. However, the ongoing three-year cooperative research project shows Wisconsin stocked fish have an above average likelihood of surviving to harvest and are being caught in comparatively large numbers in an area stretching from Door to Kenosha counties.

At the same time, state anglers are benefiting from natural reproduction of wild fish from Michigan streams and tributaries to Lake Huron.

“Wisconsin offers a world class recreational fishery and DNR’s Lake Michigan stocking efforts continue to play a key role in sustaining this resource and its multimillion dollar economic impact,” said DNR Secretary Cathy Stepp. “This study reinforces the importance of our high quality hatchery efforts while supporting the value of ongoing investments in our fisheries operations.”

Dave Boyarski, DNR fisheries supervisor for northern Lake Michigan, said the department has been working closely with the Fish and Wildlife Service’s Fish Tag and Recovery Lab near Green Bay to tag chinook fingerlings as well as collect and analyze the tags from the heads of recovered fish. Chinook salmon tagging for the recent multistate project began in 2011 and the analysis involved some 46,000 recovered tags.

The coded wire tags resemble tiny pieces of pencil lead and are inserted through a mechanized process that has proven more efficient and less stressful to the fish than previously used hand-held methods. During 2014 alone, state fisheries managers in Wisconsin, Illinois, Indiana and Michigan tagged and released more than 2.9 million chinook salmon bound for the waters of lakes Michigan and Huron. Wisconsin DNR’s Wild Rose and Kettle Moraine Springs hatcheries contributed about 824,000 of that total.

Illustrating the excellent returns of fish stocked by Wisconsin’s hatcheries, from 2011 to 2013 Wisconsin provided 38 percent of all the chinooks that were stocked in Lake Michigan. Yet from 2012 to 2014, Wisconsin stocked fish accounted for some 49 percent of stocked fish harvested throughout the lake and 57 percent of the stocked fish taken in Wisconsin waters.

The results of the analysis show the fish stocked by Wisconsin DNR appear to survive at better than average rates and account for a relatively large percentage of the stocked chinook salmon harvested throughout Lake Michigan, Boyarski said. In addition, anglers are benefiting from strong reproduction among wild chinook, which accounted for about 60 percent of the total harvest throughout Lake Michigan in 2014.

Brad Eggold, DNR fisheries supervisor for southern Lake Michigan, said the study demonstrates the benefits of Wisconsin’s investment in the Wild Rose Fish Hatchery where the majority of Wisconsin Chinook salmon are reared. The results also reinforce the importance of multistate cooperation and the involvement of anglers throughout the region.

“We greatly appreciate the opportunity to work with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife team to collect this data, which will inform our management efforts going forward,” Eggold said. “We also want to thank the many thousands of anglers and other partners who aided this effort by collecting the tens of thousands of fish heads needed for the analysis.”

Charles Bronte, senior fisheries biologist with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, said the multistate effort was initiated in an attempt to understand the growth and survival of chinook, their movement throughout the connected waters of lakes Michigan and Huron and levels of natural reproduction. These measures are critical to the DNR for managing chinook in response to a changing base of forage fish.

“If we’re going to find the answers, we need this kind of coordinated research among all the states in the region that stock chinook because the fish don’t stay in one place,” Bronte said. “What we learn from this work will help guide best practices for producing healthy fish throughout the region, maximize returns and provide further insight into the conditions essential for these fish to thrive.”

Other important insights gleaned from the work include the fact that natural reproduction now accounts for some 60 percent of the chinook population from the combined year classes 2011, 2012 and 2013. However, lower lake levels and stream flows during 2012 and the subsequent harsh winter contributed to a reduction in successful natural spawning and survival for the 2013 year class of chinook, which was only 37 percent wild fish.

The team of experts said more work and more time will be needed to assess whether natural reproduction will rebound following the difficult 2013 cycle. Disruptions in the lake’s food web caused by invasive mussels and other species also bear further monitoring and will influence future management decisions.

“The study reinforces the importance of science-based management efforts and provides a wealth of information that we intend to share with our stakeholders,” Boyarski said. “In the months ahead, we’ll use what we are learning to examine our own management practices and implement strategies that increase the return on our stocking and management efforts going forward.”

To learn more about the research and the Lake Michigan fishery, search the DNR website dnr.wi.gov and search “Fishing Lake Michigan and “chinook salmon research.”

FOR MORE INFORMATION CONTACT: Dave Boyarski, DNR northern Lake Michigan fisheries supervisor, 920-746-2865; David.Boyarski@Wisconsin.gov; Brad Eggold, DNR southern Lake Michigan fisheries supervisor, 414-382-7921, Bradley.Eggold@wisconsin.gov; Charles Bronte, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service senior fisheries biologist, 920-412-8079, Charles_Bronte@fws.gov; Jennifer Sereno, DNR communications, 608-770-8084, Jennifer.Sereno@wisconsin.gov