Little things turn out to be big deals in Chesapeake Bay predators’ diets

Today’s feature comes to us from Karl Blankenship, long-time editor of Bay Journal, detailing a topic that is beginning to be understood as critical to gamefish populations everywhere—the forage the fish eat.

Analysis finds invertebrates, tiny anchovies are critical in Chesapeake food web

By Karl Blankenship, Editor

Bay Journal; www.bayjournal.com.

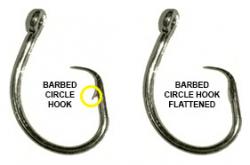

Menhaden are caught in a purse seine net

Menhaden are caught in a purse seine net. An analysis of the diets of five major Bay predators found that menhaden was important for only one, striped bass, and even for them, the bay anchovy was more important. (Dave Harp)

t-studied estuary in the world, but a group of scientists attending a recent workshop were surprised about how little they knew about what predatory fish eat.

After all, menhaden — dubbed by some as the “most important fish in the sea” would also be the “most important” fish in the Bay, right?

Apparently not. That honor, were one species to be singled out, might belong to the tiny bay anchovy — a fish that rarely grows more than 3–4 inches in length and typically doesn’t live longer than a year.

“They’re the most abundant fish in the Bay,” said Ed Houde, a fisheries scientist with the University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science, who helped organize the workshop. “They’re really important in the Bay’s food web.”

An analysis of 12 years of Baywide diet information for five major predators prepared for the workshop found that bay anchovy was a significant portion of the diet for four of those species. Menhaden was important for only one, striped bass, and even for them, bay anchovy were more important.

“Menhaden came out not as high on the list as people thought it was going to be,” Houde said. “It was an important prey, but it certainly wasn’t in the top three or four.”

Even more significantly, the analysis showed that the Bay’s food web is less of a fish-eat-fish world than popularly thought, even among many scientists. A host of unheralded species, from worms to clams to crustaceans, are major food sources for the Chesapeake’s predatory fish.

Those were some of the findings that came out of the workshop conducted by the Bay Program’s Scientific and Technical Advisory Committee late last year. The workshop focused on the question of whether the Bay produces enough food, or “forage,” to adequately support its predator population. The workshop stemmed from a commitment in the 2014 Chesapeake Bay Watershed Agreement that called for assessing the “forage fish base.”

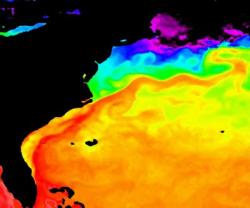

It’s a question conservation groups, scientists and fishery managers are increasingly asking for oceans and coastal areas around the globe: Are there enough herring, anchovies, menhaden and similar species to feed predatory fish, marine mammals, fish-eating birds and, in many cases, to support major fisheries?

It was once thought those small schooling fish were so abundant that they could not be overfished. Around the world, they account for about a third of all fish harvested, after which they are processed for oils, fish meal, livestock feed and other products. A 2012 report by the Lenfest Forage Fish Task Force, prepared by scientists around the world, including Houde, called for global harvests to be cut in half to protect both forage species and the many predators that depend upon them.

Similar questions about the forage base have been raised around the Bay. Anglers have complained for years that striped bass were underfed because of a lack of menhaden, and watermen have contended that large numbers of striped bass and other fish looking for food ate too many blue crabs.

Fishery management over the years has sought to maximize the production of predators like striped bass. Other predators have been introduced, sometimes accidentally, such as snakeheads, at other times deliberately, to give anglers new pursuits, such as blue catfish and flathead catfish.

Populations of many fish-eating birds, including bald eagles, osprey, great blue herons and cormorants are at or near record highs, at least compared with recent decades. Meanwhile, some prey thought to have been important historically, such as river herrings and American shad, are at historic lows.

Invertebrates ‘key’ food source

The forage workshop, which followed the new Bay agreement commitment by a few months, was aimed at reviewing what data were available about forage in the Bay and identifying new information that might be needed to guide future forage fish management — and to ensure high and sustainable production of their predators.

But along the way, workshop organizers began to realize that in the Chesapeake, the emphasis just on “forage fish” might be less important than it is for some other areas.

That stemmed from an analysis done for the workshop that examined the diets of five predators thought to be good indicators of predator food demand in different areas around the Bay. The predators in the analysis included striped bass, summer flounder, Atlantic croaker, clearnose skate and white perch.

The analysis drew on 12 years of data from the Chesapeake Bay Multispecies Monitoring and Assessment Program (ChesMMAP), conducted by the Virginia Institute of Marine Science, which collects fish at locations from the mouth of the Bay to near Baltimore five times a year.

Since 2002, the survey has captured 391,000 fish, and measured 285,000. Biologists have examined the stomach contents of more than 35,000 fish, representing 94 species, to determine what the fish had been eating.

A type of forage was considered “important” if it accounted for more than 5 percent of the food in any predator species in at least one survey. It was “key” if it accounted for 5 percent in more than one predator.

More than half of the 20 forage groups identified as “key” or “important” turned out to be invertebrates such as mollusks, worms and crustaceans.

For instance, mysids, a small shrimp-like crustacean, was the most common food consumed by summer flounder, measured by weight, the second most common consumed by striped bass, and the third most common prey of Atlantic croaker. Polychaete worms were the most common prey of Atlantic croaker and white perch, and the third most important for striped bass.

In other coastal areas, “the invertebrates are not the big issue — it is the small schooling herring and anchovies or what have you,” said Tom Ihde, an ecosystem modeler with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Chesapeake Bay Office, who helped organize the workshop.

Forage fish vs. forage base

Bay Anchovy

In real life, the bay anchovy behind Ed Houde, a fisheries scientist with the University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science, only grows to be 3–4 inches long. (Dave Harp)

Ihde and Houde said much of the previous work concerning forage has focused on predators in ocean fisheries. Those fish are often larger, and primarily consume small fish. Also, much of that focus has been in places such as the West Coast, which lack large estuarine feeding grounds like the Chesapeake Bay.

In the Chesapeake, the predators are often smaller — the largest striped bass generally are here only a few weeks of the year to spawn — and much of the food of the smaller, resident striped bass consists of a variety of bottom-dwelling organisms. As a result, what started out as a discussion aimed at addressing forage fish turned into one focused on the entire forage base.

In fact, the importance of soft-bodied organisms like worms is likely understated when fish stomach contents are examined, Ihde said. “Some of these invertebrates are digested quickly and are probably even more important than our analysis would show because they very quickly turn into unidentifiable goo,” he said.

That said, workshop participants said in their recently released report that menhaden should still be considered a key forage species because the species is important to large striped bass for whom the Bay is a critical spawning area, even if they are only here part of the year. Menhaden are also considered important prey for larger individuals of other large predatory fish such as weakfish and bluefish. And menhaden are likely important for other species, such as fish-eating birds, workshop participants said.

“There’s a general perception that it is all about menhaden,” Ihde said. “They are important. But we can’t forget about all these other things that in some cases are more important to our current system.”

And those other things add to the complexity of understanding, and ultimately trying to manage, the Bay’s food web.

Some organisms not typically thought of as forage turned out to be important in the Bay, such as the young of croaker, weakfish and spot — adults of which are generally considered predators.

“It was a big surprise to me to see something like young-of-the-year weakfish show up as one of the more important prey in the diets of predators,” said Houde, who has participated in several forage fish studies in recent years.

Scant data for tributaries

But the total picture is far from complete. The ChesMMAP surveys only cover the mainstem of the Chesapeake. There is little information available about tidal tributaries.

Those areas are important nurseries for many fish — and are also home to a rapidly growing population of predatory blue catfish. Although some studies are under way to better understand the diet of blue catfish, much less is known about the forage base and food demand by predators in those areas.

Because of those limitations, workshop participants suggested the data from ChesMMAP may under-represent the importance of some forage species such as American shad, river herrings, mummichog, killifishes, gizzard shad, silversides and some small bivalves, which tend to be found in low-salinity areas.

Even less is known about shallow water of less than 2 meters, especially in habitats such as underwater grass beds and marshes, which biologists think may be particularly important for forage production, and where survey boats have a hard time operating.

And the ChesMMAP data have their own limitations. It is a trawl survey, so it collects fish mainly from the bottom, and collections from its gear under-represents both the largest and smallest fish.

The survey is being modified in coming years to collect more samples from higher in the water column and from the benthic invertebrate communities at its collection sites.

While that should refine its information, it is not likely to dramatically change overall conclusions, as other — albeit smaller — surveys examined in the workshop analysis found similar results.

“Our hope is it will lead to a much better understanding of the ecosystem,” said Chris Bonzek, the VIMS scientist who oversees the ChesMMAP survey and who prepared the forage analysis for the workshop. “But we are not going to all of a sudden see that bluefin tuna are the most important predator in the Bay.”

A more complete picture

Because predators are eating so many types of prey — many of which are poorly studied — it’s difficult to characterize the current status of the Bay’s forage base. But, with support from the Bay Program’s Sustainable Fisheries Goal Implementation Team, Houde and several colleagues are reviewing existing information to start piecing together a more complete picture of forage abundance and predator demand.

With information gleaned from the ChesMMAP analysis and other sources, they are assessing the relative abundance of different forage groups in regions of the Bay to see if there are trends in the overall amount and availability of prey, or in the relative abundance of the different types of forage.

In addition, they are looking at stomach content data from major predator fish species to begin to estimate the amount and kinds of forage they are consuming.

That information will start addressing the fundamental questions of how much forage is consumed by predators, what type of forage is most important in different regions of the Bay and how much change has taken place over the years. Ultimately, it will help answer the question of how much food is needed to support the Bay’s predators, both now, and in the future.

“While we are not close to getting that answer, it is the direction we are heading in,” Houde said. “Providing estimates of consumption and forage demand is something we would like to be able to deliver to managers in the next decade.”

A ‘balanced’ ecosystem

Figuring out how to use that information to maintain a “balanced” ecosystem will be a challenge for managers as populations of many forage species vary widely. For instance, the numbers of bay anchovy can fluctuate tenfold from year-to-year — they can live up to three years, but most are eaten by predators within a year — so the relative success of annual reproduction drives their overall abundance. Likewise, the numbers of young croaker, weakfish and spot available to be eaten depend on year-to-year reproduction success.

When the issue moves beyond fish to the broader forage base, the level of complexity increases. Many bottom-dwelling species can be sensitive to extended periods of low oxygen, so a large seasonal “dead zone” can reduce overall abundance, and even eliminate species, from some areas. “If it is a bad hypoxia year, the benthic invertebrates cannot get up and swim away like the fishes,” Ihde said.

The loss of underwater grass beds, coastal marshes and oyster reefs have reduced the amount of habitat available for many forage species. The hardening of shorelines, development of land adjacent to the Bay and its tributaries, sea-level rise and climate change will likely cause continued habitat losses, the workshop report said.

At the same time, predator populations are constantly changing — and not just the fish.

Around the Bay, the populations of fish-eating birds such as eagles, osprey and blue herons are large — and growing. The Bay’s population of double-crested cormorants, which was almost nonexistent four decades ago, is nearly 5,000 today. That’s enough cormorants to consume 300 tons of fish annually, according to the workshop report.

Overall, the fish demand of birds around the Bay is largely unknown, Houde said. Birds, though, could be one of the first indicators of stress if there were a problem with the Bay’s forage base. Houde noted that research in other areas has shown that when forage fish populations decline by a third of unfished levels, the populations of fish-eating birds may drop precipitously.

Protecting forage fish

Other than menhaden, most of the forage species in the Bay are not actively managed fishery species. Menhaden have been increasingly regulated in recent years by the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission, which manages migratory fish along the coast. The commission is working to establish new harvest goals in the next several years that recognize the role of menhaden as prey for predators.

The abundance of other forage can be influenced by a range of actions aimed at improving environmental conditions and protecting habitat, the workshop report said.

For instance, reducing nutrient pollution could reduce the size and duration of dead zones — Bay water quality standards were written to promote a greater diversity of benthic creatures as well as larger, longer-lived species.

Other actions can help protect habitat important for forage species, the report said, such as limiting the use of bulkheads and other hardened shorelines that degrade local habitats, and controlling development near the shore, which is increasingly linked to the lost or reduced production of benthic species.

Forage could also be protected by reducing some predator fish populations, such as snakeheads or blue catfish, but managers have little control over other predators, such as birds.

But the emerging information could offer other opportunities for management. The recognition that the little bay anchovy plays a relatively big role in the Bay food chain could promote efforts to better understand it, Houde said.

“The anchovy is so tiny that most people have discounted it as the target of a directed fishery,” he said, “but there have been proposals for bay anchovy fisheries in other areas along the Atlantic coast.”

Although he said such a proposal is unlikely for the Bay, fishery managers might want to consider policies to prohibit a future fishery in recognition of the bay anchovy’s importance to other species.

“Sometimes,” he said, “in the case of a forage fish, it is easier to develop and implement management policies before there is a fishery.”

The workshop report, “Assessing the Chesapeake Bay Forage Base: Existing Data and Research Priorities,” is found at the Scientific and Technical Advisory Committee website, chesapeake.org/stac/; click on “publications.”

The Bay Program’s management strategy for its forage fish outcome is found at chesapeakebay.net/chesapeakebaywatershedagreement/goal/sustainable_fisheries.

What’s on the menu for Bay’s predators

Drawing on information from the Scientific and Technical Advisory Committee’s workshop report, the Management Strategy for the Chesapeake Bay Watershed Agreement’s Forage Fish outcome preliminarily identified these as the Bay’s key forage species and groups for a wide variety of predators:

Bay Anchovy

Polychaetes

Mysids

Amphipods

Isopods

Mantis Shrimp

Young Spot

Young Weakfish

Sand Shrimp

Young Atlantic Croaker

Razor Clams

Atlantic Menhaden

These species were recognized as potentially important forage groups or species, but were not identified as the top contributors to the diets of predatory fish by information presented at the workshop:

American Shad

River Herring

Atlantic Rock Crab

Atlantic Silverside

Blackcheek Tonguefish

Blue Crab

Flounders

Gizzard Shad

Kingfish

Lady Crab

Macoma Clams

Mud Crab

Mummichog

Killifishes

Small Bivalves

Carl Blankenship

About Karl Blankenship

Karl Blankenship is editor of the Bay Journal and Executive Director of Chesapeake Media Service. He has served as editor of the Bay Journal since its inception in 1991.

Read more about Chesapeake Bay at www.bayjournal.com.