Rare Shark Tagged Near Cuba “Phones Home” Near U.S. Coast

by Hayley Rutger, Mote Marine

from The Fishing Wire

A rare longfin mako shark satellite-tagged near Cuba recently “phoned home” off the U.S. Atlantic coast, say Mote Marine Laboratory scientists and colleagues who tagged the mako during the first-ever expedition to satellite-tag sharks in Cuban waters.

The shark was tagged on Feb. 14 offshore of Cojimar in northern Cuba, during an expedition by scientists from Mote, a world-class marine research institution in Sarasota, Fla., from Cuba’s Center for Coastal Ecosystems Research, the University of Havana, and other Cuban institutions, and from the Environmental Defense Fund, which facilitates U.S.-Cuban collaborations in science and conservation.

The expedition — including satellite-tagging the longfin mako — was filmed by Tandem Stills + Motion, Inc. and Herzog Productions and featured in early July in “Tiburones: The Sharks of Cuba,” a program of Discovery Channel’s Shark Week. An updated version of the program with these fascinating findings will air at 7 p.m. on Aug. 30 as part of Shweekend on Discovery.

The team also tagged three silky sharks in the Jardines de la Reina (Gardens of the Queen) National Marine Park off Cuba’s south coast. Each tagging was a dream come true for the U.S.-Cuban scientific team that had worked for years to obtain permission and resources to place the first satellite tags on sharks of Cuba.

“Our dream was to be able to deploy satellite tags on sharks in Cuban waters, on both the north and south coasts, in an equal partnership of Cuban and American research teams,” said Dr. Robert Hueter, Director of the Center for Shark Research at Mote. “We were able to accomplish these goals for the first time with this expedition.”

Tagging the longfin mako was especially exciting. This species generally inhabits deeper waters and poses more unanswered questions than its shallower-water cousin, the shortfin mako.

“There is a ton known about shortfin makos and almost nothing known about the longfin, which wasn’t described until 1966 by the Cuban ichthyologist Dr. Dario Guitart Manday,” Hueter said.

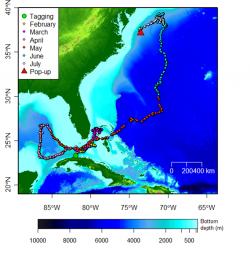

“Maximum likelihood track” of the longfin mako shark tagged by the U.S.-Cuban team off the north coast of Cuba in February 2015. Credit Mote Marine Laboratory.On July 15 the longfin mako’s tag separated from its tether to the shark, as it was programmed to do, floated to the surface and began sending its archived data to Mote scientists via satellite. Since then, the research team has received and analyzed all the data to accurately document the shark’s movements.

After being tagged in mid-February, the shark departed from waters off Cojimar in northern Cuba, traveled with the Gulf Stream current between Florida and the Bahamas, and then doubled back into the eastern Gulf of Mexico, where it swam in a clockwise loop in April and early May between Florida and Mexico’s Yucatan Peninsula. Then in May the shark swam back along the Gulf Stream, through the northern Bahamas and into deep waters of the open Atlantic, where it proceeded north until it was offshore of New Jersey in late June. Finally, it headed south to waters off Virginia, and its tag popped off and surfaced about 125 miles east of the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay. The total track covered nearly 5,500 miles in five months, averaging about 36.5 miles per day.

This shark is the second longfin mako tagged by Mote, and one of just a few tagged worldwide. Its travels are raising exciting questions.

“The amazing thing is this longfin mako’s tag popped up in nearly the same exact location as another one we tagged in the northeastern portion of the U.S. Gulf of Mexico a few years ago,” said John Tyminski, who processed the satellite data and was joined on the expedition by Mote scientists Hueter and Jack Morris. “The movement patterns of the two sharks are remarkably similar: both sharks were in the eastern Gulf in April/May, showed comparable movements through the Straits of Florida, and ended in a similar area off Chesapeake Bay in July. Both tags came off during the month of July and both sharks were mature males. Clearly there’s something in that location that’s attracting mature males in summer.”

One possibility is mating, but satellite tags alone cannot confirm that or rule out other possibilities like feeding or just passing through.

The tag also showed the mako spent a majority of its time in depths of less than 1,640 feet (500 meters), staying mostly deeper during the day than at night, but the shark made some extreme dives including one to 5,748 feet (1,752 meters), more than a mile deep. “At that depth the shark is dealing with extreme cold, close to freezing,” Hueter said. “The data from this tag will help us understand why these sharks are diving so deep and how they are dealing with such cold temperatures.”

Two of the silky sharks reported back when their tags popped off early, about a month after the expedition. The tags revealed that the sharks had made movements away from the inshore reef area where they were tagged and into deeper offshore waters, spending most of their time in the upper water column but also diving during the day. One of the sharks reached a maximum depth of 2,073 feet (632 meters). The remaining silky shark wears a real-time satellite transmitter that can relay data to scientists when the shark’s fin surfaces — but so far it has tended to stay below.

The longfin mako’s results remain the most tantalizing — shedding light on the life of a rare species while demonstrating an important point: The U.S. and Cuba are fundamentally connected by the sea.

“The fact that these sharks go back and forth among the waters of multiple nations – in this case, Cuba, the United States, the Bahamas and Mexico – shows the importance of coordinating our fisheries sustainability and conservation efforts on a multilateral, even global, scale,” Hueter said. “Clearly it is important for the U.S. and Cuba to work together to protect vulnerable marine resources like these rare and depleted species of sharks.”

Founded in 1955, Mote Marine Laboratory & Aquarium is celebrating its 60th year as an independent, nonprofit 501(c)3 research organization. Mote’s beginnings date back six decades to the passion of a single researcher, Dr. Eugenie Clark, her partnership with the community and philanthropic support, first of the Vanderbilt family and later of the William R. Mote family.

Today, Mote is based in Sarasota, Fla. with field stations in eastern Sarasota County and the Florida Keys and Mote scientists conduct research on the oceans surrounding all seven of the Earth’s continents.

Mote’s 25 research programs are dedicated to today’s research for tomorrow’s oceans, with an emphasis on world-class research relevant to the conservation and sustainability of our marine resources. Mote’s vision also includes positively impacting public policy through science-based outreach and education. Showcasing this research is Mote Aquarium, open from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. 365 days a year. Learn more at mote.org.

Contact Us:

Mote Marine Laboratory and Aquarium, 1600 Ken Thompson Parkway, Sarasota, Fla., 34236. 941.388.4441