| Here are some interesting tips on jackplates for bass and flats boats, from noted tournament pro and flats angler by Bernie Schultz. from the Fishing Wire  Ask any touring pro if a hydraulic jackplate is worth the money, and I’d bet their answer would be an emphatic “yes!” On the Bassmaster Elite Series, they’re considered essential equipment … for multiple reasons.Although they may be a bit pricey, hydraulic jackplates can vastly improve the performance of your bass boat or flats boat — both at the top end and in the ability to run shallower at low or high speeds. They can even improve the ride. A simple touch of a lever or toggle switch allows the operator to raise or lower the outboard engine while under power, at any speed. Combine that with the engine’s power trim and you’ll realize advantages beyond the obvious. Skinny as she goes Consider bedding season when, on some lakes and rivers, you’re dealing with vast, shallow flats — places where the fish may concentrate only in small areas. Covering water is required to find those fish, and using a trolling motor to do it can be tedious and time consuming. Idling with the main engine makes much more sense. But without a jackplate, you would have to trim the engine up, which squats the stern and bogs the engine down, making maneuvering much more difficult … not to mention the added disturbance it causes in situations requiring stealth. With a hydraulic jackplate, you can raise the engine up high and adjust the trim to give the boat a flatter attitude. This not only improves maneuverability, it allows you to increase idle speed to cover more water while creating less disturbance. Hydraulic Jackplates can improve your boat’s performance in multiple ways. The ability to raise the engine also allows you to plane off in shallow water — much shallower than would be possible with a fixed engine height. This is a huge advantage, especially in places that normally require long idle times to reach adequate planing depths. A trick I learned from flats fishing in saltwater is to take advantage of the clockwise rotational lift of a spinning prop. By turning the steering wheel all the way to the left (which puts the leading edge of the skeg facing right, the same direction of the prop’s clockwise rotation) you then realize added lift when applying full throttle. This kicks the stern around and actually throws out a small wake, which provides a slight increase in water depth for the prop to bite in. In addition, with the engine cocked at an angle, you minimize contact with lake bottom as the boat leans to one side. As the hull begins to plane, you gradually lower the engine to submerge the water pickup. (This is critical, as you do not want to starve the engine for water for any length of time.) Using this counterclockwise maneuver, the boat will usually spin to a full circle before reaching planing speed. And it happens quick, so it’s a good idea to plan your exit route ahead of time. Once up and running, you simply adjust the trim and engine height to your liking. Here’s a short video that demonstrates the technique.  Here’s an aerial view of a boat performing a circular, shallow-water hole shot. Notice the mud trail. Here’s an aerial view of a boat performing a circular, shallow-water hole shot. Notice the mud trail. Digging deeper While hydraulic jackplates prove beneficial in the shallows, they can also enhance performance in deep water. Because they set the engine farther from the transom (usually up to 12 inches), it effectively increases the overall length of the boat — which, in turn, makes it bridge more water. And that’s good, especially in rougher conditions. But the biggest advantage is the additional leverage they provide. By dropping the jackplate and tucking the engine under, you can greatly improve handling in choppy water. This added “pinch” on the hull and motor will force the bow down to create a flatter ride. If you have ever plowed through rough seas in a strong headwind, then you know how critical this can be. Bass boats are notoriously stern heavy. When you factor the weight of multiple batteries, an onboard charger, fuel, livewells, Power-Poles and gear, keeping the bow down can become a serious challenge, and a hydraulic jackplate will compensate for that. Need for speed For the totally performance minded, jackplates also add top-end speed with better handling. By lifting most of the lower unit out of the water, you minimize torque at the wheel and decrease drag. Add a bit of trim and the bow will lift while increasing speed. The trick here is finding just the right height with the plate and proper trim to reach the ideal RPMs … all while maintaining sufficient water pressure. Every boat will be different, so it may take some tweaking with the right prop and engine position to realize your boat’s top-end speed. There are a number of quality jackplates on the market, including CMC, SeaStar, Bob’s Machine Shop and T-H Marine. And most of these brands offer multiple offset sizes (6, 8, 10 and 12 inches are common) capable of handling the weight of large-block outboards. I run a 12-inch Atlas by T-H Marine. It’s quick, quiet and self-contained with no messy remote pumps or hoses, and it works well under power in a chop. I also run one on my saltwater skiff and have for years with zero issues. Most brands offer a console gauge to monitor engine height, but they won’t tell you if your water pickup is submerged and functioning. For that you’ll need a reliable water pressure gauge. Believe me; you can jack an engine to the point where it’s starving for water. If you do that for more than a few seconds at speed, you can fry your engine. One last tip: If you’re using your jackplate for top end performance, I highly recommend mounting a lever-style switch on the steering column. Just like the blinker switch in your car, it’s quick and handy. In fact, I suggest mounting a matching trim lever on the opposite side. That way, both hands are always on the wheel, which will ensure a much safer boating experience. Follow Bernie Schultz on Facebook and through his website  |

Monthly Archives: November 2020

Falling Leaves and Pecans

When I was young I watched leaves start falling with mixed emotions. The big pecan trees in our yard dropped what seemed like tons of leaves that needed raking. But they also dropped delicious nuts.

By the time I was eight years old I was spending hours with a rake in my hands. Before that, I would help pick up pecans, dropping them into a small bucket then dumping it into a croker sack. We would go over the yard picking up pecans first, then rake the leaves into the ditch in front of the house.

Times were much more peaceful back then. The quiet whoosh of the rake was soothing, unlike the high-pitched whine of leaf blowers now.

After raking the leaves, daddy would take a fishing pole and knock the lower limbs to make more nuts fall so we had to go over the yard again to pick up newly exposed nuts as well as the ones he shook loose. When I was a little older he would let me climb the tree and shake the limbs I could get to without falling with the nuts.

The huge tree in front of the house was hard to climb since the lowest limb was way above my head and the limbs were so big they were hard to shake. But four other trees were smaller and I could reach lower limbs, climb up to each limb, stand on it while holding tight to a higher limb and jump up and down. It was effective except for the highest limbs.

We always burned the leaves in the ditch. I really enjoyed that part of the process. I still get warm, good memories when I smell leaves burning in the fall. We would stand around the ditch with our rakes, trying to avoid the smoke, and make sure the fire stayed in the ditch.

When the pile burned down, daddy would take a pitchfork and turn the embers over, exposing lower leaves that had not burned from lack of air. This made sure they all burned.

After the fire was mostly out I would get down in the ditch and rake around for pecans we had missed. There were always some under the ashes and, although some were burned too much, many were roasted just right. I don’t think I have ever eaten a better pecan than those that were still in the shell and hot from the fire.

We repeated this process three or four times each fall, filling many 50-pound sacks with nuts. We kept them separated by variety. One tree had what we called “thin shell” pecans, nuts with very thin, easy to crack shells. Another tree we called “peewee” pecans, small nuts that were half the size of the other trees.

I hated picking them up since it took forever to fill a bucket. But for some reason they brought more money per pound than the bigger nuts. We sold many pounds of pecans, taking them to a buyer in Augusta. We often had a half dozen 50 pound bags to deliver.

Although we sold many of the nuts, we cracked and shelled many pounds for our own use. All summer long we had sat around the TV at night shelling peas and butterbeans, but in the fall we did the same with pecans.

Daddy would take the nuts and crack them with a nutcracker, then mama, Billy and I would shell them, Daddy could crack them so most of the shell came off easily but without damaging the nut.

The goal was to get out whole halves. The halves went into one big bowl while the pieces went into another, keeping them separate for different uses. The halves had to be worked on to get the thin bitter string out of the groves on top of the nut. We had special picks to scrape them out.

Each night as soon as we got enough mama would cover a baking sheet with nuts, put them in the oven and roast them. While shelling them we ate the warm, salted nuts.

I had a “pet” red ant bed in the ditch where we burned the leaves and I always worried the fire would kill them. But as soon as the ground cooled they would dig out of their bed and start working, clearing the tunnels and making a small circular mound.

All summer I would kill flies and take them down to the bed and feed the ants. I loved watching an ant find the dead fly and carry it back to the tunnel. I could sit for hours watching them move dirt grains around and make their home.

Although they often crawled on me, I never got bitten by one. These ants were big, much bigger than the smaller black ants that lived around the house and made smaller mounds. I still do not know what species of ant they were but they fantasticated me.

Back in those days simple things kept kids interested. And we always had chores to do. I wonder if any kids now have any similar experiences.

Carp: The Gamefish in Our Backyards

Add an underwater camera to your arsenal and learn where the giants await. Carp specialist Nathan Cutler calls his Aqua-Vu his most important learning tool. Carp specialist Nathan Cutler calls his Aqua-Vu his most important learning tool.from The Fishing Wire Crosslake, MN – Nathan Cutler remembers the first big carp he ever hooked. Standing on shore that day in 1999, exhausted and beaten, Cutler lamented the battle, the lost fish and the damage it had inflicted upon his gear. Among the casualties: The carp had stripped 150-yards of line from his spool, straightened the hook, melted the gears in his reel, burned the eyelet inserts on his rod and stripped the reel right off its seat. That was the day the lifelong Canadian angler decided to learn all he could about this massively under-appreciated creature, the common carp—and that meant immersing himself in the underwater domain of his favorite fish. “I’ve learned more from my Aqua-Vu HD underwater camera in a year than I probably could have in decades of regular fishing,” says Cutler, who operates ImprovedCarpAngling.com and a corresponding YouTube channel featuring spectacular underwater carp footage. “As a scientist, I love to test out every new tactic, bait and rig and watch how fish react. Not only does the Aqua-Vu camera allow me to record the fish in their natural environment, but more importantly, I can view things as they happen in real time. This lets me adjust rigs and baits on the fly to see what works and what doesn’t. ”At home near the crystalline waters of Lake Huron and the St. Lawrence River, Cutler enjoys immediate access to numerous shore fishing spots, each one hosting concentrations of carp up to 40-pounds or more. “I have no idea why more anglers don’t target them,” wonders Cutler. “Carp are one of the largest, hardest-pulling catch-and-release species that live in abundance close to shore. You can set up pretty much anywhere along the shoreline here and enjoy a very successful day of fishing.” On most of his shore spots, including breakwalls and marina docks, Cutler finds it easy to deploy his Aqua-Vu HD10i camera by dropping it right off the bank, dock or pier. On shallow flats, Cutler simply wades out and places the camera by hand. He then casts his fishing rig and bait to lie within several feet of the camera lens. “One cool thing about carp angling, which makes using the camera very easy, is that you usually bait or chum an area and wait for fish to come to you,” he notes. “I’ve designed a mount for the Aqua-Vu that acts as an anchor, positioning the lens at any angle I want, adjacent to my fishing area. I use the Aqua-Vu XD Pole Mount attached to a base of concrete poured into a 5-gallon bucket.” Instructions for Cutler’s camera stand can be found in a YouTube video explaining the setup. On-Screen Observations In the past year since his first underwater carp forays, Cutler has observed some truly fascinating fish behaviors, as well as the hidden habits of other aquatic animals. “I’ve seen cormorants and otters swooping at baitfish in 25 feet of water,” he says. “I see salmon all the time that seem intrigued by the camera and like to bump and knock it over. Smallmouth bass often stop and look directly into the lens before moving on. When all the fish suddenly clear out, it usually means a big pike is about to swim through the lens. You also can’t help but notice all the round gobies down there. In real time they’re difficult to spot because they move in bursts, stop and disappear into bottom. When I speed up the recorded footage it looks like the whole bottom is moving.”  Aqua-Vu HD10i Underwater Viewing System Aqua-Vu HD10i Underwater Viewing SystemCarp, known by their most ardent angling fans as highly intelligent, discerning and wary, exhibit some fascinating underwater preferences. “I’ve been a fan of the simple hair rig for years and thought by presenting my bait a few inches above bottom over my pre-baited areas, fish would notice it quicker and I’d catch more fish. “Actually, the camera showed me that the fish would nudge the rig, appear to feel the hook and avoid it altogether. Only about one of every ten fish I saw on screen took the bait without nudging the rig first. That was a huge revelation. As soon as I pinned the hook to the bottom, with the bait barely floating above, my catch rate nearly doubled.” Cutler’s camera work also revealed that carp often detect and avoid his fishing line. “I’ve watched carp on camera detect my line and bolt off in the opposite direction. To combat this, I now use a ‘back lead,’ or a a second weight attached to your line nearest the rod tip, pinning the line to the bottom so fish are less likely to see it. Line visibility isn’t something many anglers ponder, but with carp, it can be a major factor. ”The camera screen further surprised Cutler with the sheer number of fish haunting his pre-baited areas. “Many days I’ll be sitting without a nudge on my line. I’ll drop the camera to see if my rig and bait are presented properly and I’m always shocked by the number of fish visiting my baited area—up to 15 different carp moving in and out of frame, taking mouthfuls of bait as they feed.”  The XD Pole Adaptor allows for a variety of viewing angles and applications The XD Pole Adaptor allows for a variety of viewing angles and applicationsWhat Carp Eat Cutler says the camera has proven to him that carp favor canned sweet corn from the grocery store. “No idea why North American carp love it so much, but I’ve learned if I’m targeting a new area, I always toss in a can of Jolly Green Giant and lower the camera. With other baits, it can take a long time and a lot of chumming before carp stop to investigate or eat it. “If you pre-bait an area for an extended duration, you can have great success catching larger fish with other baits, especially boilies (a hardened, flavored dough bait that fends off smaller nuisance fish.) Another great carp bait is a pack-bait recipe combining sweetcorn and bread, which nearly always produces fish. ”Interestingly, Cutler frequently observes carp eating mouthfuls of invasive mussels. “I see carp eating zebra mussels on the camera all the time. I believe it’s why carp grow so large in the St. Lawrence River and the Great Lakes. Come fall when temperatures drop, carp move in to deeper rocky areas with heavy mussel concentrations. Carp sometimes feed so heavily on zebra mussels that they develop red sores on the roof of their mouth resulting from the sharp shell edges.” Carp crush shells and ingest the soft-bodied mollusks with special pharyngeal teeth in their throat.“After watching carp in the same area, you begin to differentiate certain specific fish by visible characteristics, such as scale patterns, scars, etc.,” he notes. “For me, a fun challenge is to target individual big carp I see on the camera screen. We call it ‘specimen hunting.’ I’ve named one particular carp Popeye, and I’ve been trying to catch him for two years now. I see him on almost every outing, but I’m still waiting for him bite my rig. Hopefully, next time.” |

Fishing Tournaments In Early October

It was a busy three weeks in early October. I left home with my boat and camper on October 1st and stayed at Blanton Creek Park at Bartletts Ferry until Monday for the Sportsman Club Classic on Sunday.

On Monday I drove from there to Wind Creek State Park and camped for the three club tournament that weekend. Monday after the tournament Linda joined me and we fished until Thursday October 15th.

I was on the water every day but two while gone!

In the club classic, 11 of us qualified by finishing in the top eight for the year in points or fishing at least eight of the 12 tournaments last year. We landed 41 12-inch keepers weighing about 45 pounds in eight hours of casting, There were four five-bass limits and no one zeroed.

Raymond English won the classic with five bass weighing 7.55 pounds. My five at 6.63 pounds was second and I had big fish with a 2.24 pound largemouth. Wayne Teal was third with 5 at 5.92 pounds, Kwong Yu was fourth with five weighing 5.72 pounds and Jay Gerson came in fifth with five at 4.92 pounds.

At Martin we pay back each day like two one day tournaments. The first day in ten hours of fishing the 26 of us had 22 five bass limits and no one zeroed. Lee Hancock won with five weighingg 11.07 pounds and Tom Tanner was second with a limit weighing 9.92 pounds. My five at 9.84 pounds was third and I had a 3.74 pound spot for big fish. Zane Fleck plaaced fourth with five at 8.04 pounds.

On Sunday we fished for seven hours in the wind and rain, again. We had 21 limits and no one zeroed again. that’s why we love Lake Martin in October. We catch a lot if bass even if they aren’t big. Martin has millions of hungry 13 inch spotted bass!

Tom Tanner won, the only one to place in the top four both days, with five weighing 9.74 pounds. He is consistent! Don Gober came in second with five at 8.38 pounds, Raymond English placed third with five weighing 7.71 pounds and Shay Smith placed fourth with five at 7.64 pounds. JR Proctor had big fish woith a 3.45 pound largemouth.

I should have done better with all that practice!

On Friday at Bartletts Ferry I went up the river and caught five bass on four different baits in five different kinda of placees. A largemouth hit a weightless Trick worm under a dock. Then a nice spot hit a topwater plug three times on a bluff rock bank berore I hooked it. My third fish hit a spinnerbait on some wood then another largemouth hit a Senko on a sandy point. The fifth fish hit the Trick worm around grass.

Although they were all keepers there was no pattern at all that would give me confidence in the tournament.

I tried a variety of things down the lake without a bite Saturday. At 11:00 I went to a point with some brush on it I found a few years ago and caught a four pound largemouth on a shaky head. I started riding points looking for cover 15 feet deep, the depth the largemouth hit. The next one I found had stumps at the right depth and I caught a 14 inch spot on the shaky head. A third point with stumps at the right depth showed a lot of fish and I caught a small spot on a drop shot worm.

Those fish gave me some hope in that pattern, especilly he four pounder.

Sunday morning I tried some shallow points early then went to the brush on the point at 8:00 and didn’t get a bite. Hoping it was too early, I went to a dock with some brush and caught a keeper spot. A few more docks didn’t produce, so back to the point at 10:00. I immediately caugt the two pound largemouth and another keeper spot.

The next point with stumps produced two keeper spots. I had my limit by 11:00.

Although I rotated around those points the rest of the day I didn’t catch another keeper Sommething big hit my shaky head about 1:00 but it got into a stump and broke my line.

Martin is a big lake with two long arms, the Tallapoosa River and Kowaliga Creek. Wind Creek Park is way up the river. That area seems full of one pound fish and I have fished that area for 46 years so I know some good places. But a few years ago blueback herring got started in Kowaliga Creek and the fish there seem a little bigger and fatter, based on what I caught when I started fishng it a little three years ago.

I went over there the first three days of practice and found many brush piles in 25 feet of water that were covered in fish. But everything I caught were small spots. Friday morning I fished my favorite creek near the park and caugt 13 keepers in three hours. There is a shallow point in Kowaliga Creek where big bass usually feed, but it is a 25 minute run at 60 mph. And the bite ends at sunrise so I have only about 20 minutes to fish it.

The wind and rain almost made me stay near our takeoff point but at the last minute I decided to go there on Saturday. As I made the rough wet ride in the dark, watching lights on docks and danger buoys and my GPS, I kept thinking about the millions of bass I rode past. It was worth it I guess. In 20 minutes I landed six keepers including the big one on topwater.

Edward Fouker fished with me on Sunday and we made the long run. And caught nine keepers in 20 minutes. But none much over a pound Not worth the three quarters tank of gas that day!

I’m already thinking about that run next year!

Whiteoak Acorns

Whiteoak acorns have been falling like rain at my house. I blew off my driveway between my house and garage and within 48 hours I could not walk across it without stepping on acorns.

Whiteoak acorns are a wonder of nature. Big trees drop thousands of them each fall, but almost none will fill their destiny of producing another mature tree. Some will rot, but most will be eaten by wildlife. Without them some species would not survive.

Deer depend on them to fatten up in the fall for the lean winter months when food is scarce. Squirrels eat some on the spot but bury many more, sniffing them out during the winter when they, too, can not find other food. Birds of many species eat them with abandon when they are plentiful

Whiteoaks and acorns have played an important part of my outdoor life. I have spent hundreds of hours sitting under various trees, holding my .22 Remington semiautomatic rifle or my single shot .410, waiting on a squirrel to expose himself. When they came for dinner they became my dinner.

I have built deer stands in them or near them all my life. Their spreading lower limbs offer good anchors for a built stand. Most of the time I put my climbing stand near one in a popular or pine, giving myself a good shot at any deer that comes to feed.

When I was a kid, I read in one of my outdoor books that Indians ate acorns. I tried one, it was very bitter, and I immediately spit it out. Then I read the

Indians pounded them into meal, soaked the meal in water to remove the tannin, the chemical that produced the bitter taste, then used the meal for cooking.

Since there was always plenty of cornmeal in the cabinet in the kitchen, I never went to the trouble to try that.

Whiteoak wood makes good firewood and I have cut down hundreds on my property, usually one that had died, and split them up for firewood for my insert in my great room. The first five years I lived in my current house I heated it totally with the wood burning insert, putting a sheet over the stairwell going upstairs to keep the heat in the downstairs living area we used, and using fans in doorways to move the heat into other rooms.

I stopped doing that and lit the pilot light on my furnace when I was out of town for a tournament and Linda was home alone. She got sick and could not bring in firewood and keep a fire going. Even after that experience, most of my heat still came from the burning wood.

They say cutting wood for heating warms you seven times. When you cut it, load it, unload it, split it, stack it, carry it inside and finally when you burn it. I can attest to that, especially on warm fall days when I was doing all of the above except burning it!

I always wanted to be a “survivalists,” studying different kinds of edible natural plants I could gather. Mushrooms were one thing I avoided, but there is an amazing amount of food available most of the year if you know where to look. And game and fish provide plenty of protein if you can catch or kill it.

Although I have never tried most of them, there are many ways to preserve food for the winter when food is not available to gather. Like squirrels and deer, if you are going to survive in the wild, you have to store food for the winter or try to fatten up to make it through lean times.

Storing it is much better than trying to get enough fat stored to starve and burn it when no food is available.

We did that on the farm. We had a big walk in pantry off the garage and by this time of year there were hundreds of jars in it. Everything from string beans, tomatoes, potatoes to jams, jellies and preserves were canned ready for winter. Add in the freezer full of other vegetables and fruits and we ate good all winter.

I am listening to a book about a terrorist attack that destroys our electric grid and plunges the

US into chaos. Millions of people in cities run out of food in less than a week, and they have no idea what to do other than loot and steal what they want.

I think I am too old to survive on my own now, but I think I still could get by better than most. Very few people have a clue how to produce their own food. They think meat comes in nice Styrofoam packages with clear wrap, vegetables are clean and grouped in bins and canned goods magically appear on shelves.

If we ever decend into chaos like in the book millions would die. Could you survive on your own with out our food supply chain and heat from electricity and gas? Most could not.

Northeast Striped Bass Study

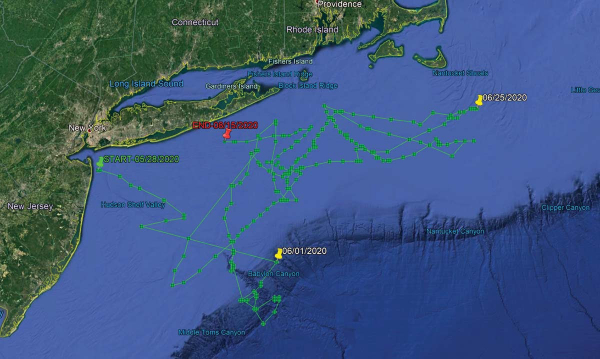

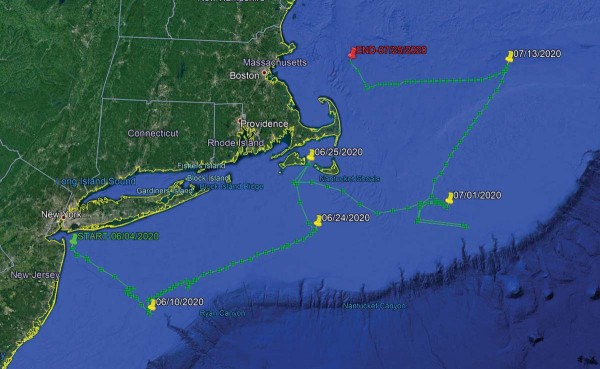

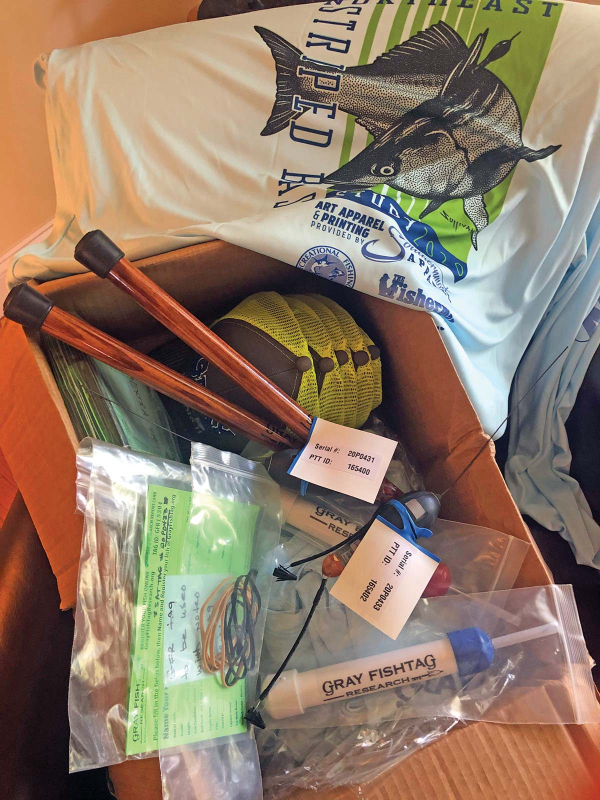

| By Jim Hutchinson, Jr. The Fisherman from The Fishing Wire  Chuck Many nets a good fish for Dave Glassberg during the spring run off the Jersey Shore during the 2020 Northeast Striped Bass Study. Chuck Many nets a good fish for Dave Glassberg during the spring run off the Jersey Shore during the 2020 Northeast Striped Bass Study.And now there are four! “If one’s an anomaly, and two’s a coincidence, will three or more show a pattern?”That was the lead sentence in our first published piece of this year (Born To Run: Hudson River To Canyon Striper) on the status of our 2019 Northeast Striped Bass Study from our January edition. By now everyone along the Striper Coast is aware of the results; two post-spawn striped bass caught by our research team at The Fisherman, Gray FishTag Research and Navionics in May of 2019, tagged with high-tech MiniPSAT devices to track migration habits during a five-month stretch, ultimately showing returns from the offshore canyons including the Hudson, Block and Veatch.Two $5,000 “pop-off” satellite tags which incorporate light-based geolocation for tracking, time-at-depth histograms for measuring diving behavior, and a profile of depth and temperature, showing two very distinct paths in waters where we typically wouldn’t expect striped bass to swim. There’s been some skepticism of course with some questing whether a big white shark gobbled up these stripers before heading east with a belly full of bass. However, the data stored inside the Wildlife Computers MiniPSAT devices – which amazingly were physically recovered by beachcombers in Massachusetts and New Jersey – shows both tagged fish were alive and swimming along the offshore grounds when the tags detached.We had grand plans in 2020, and with financial support from Navionics, Tsunami Tackle, AFW/HiSeas, Southernmost Apparel and the Recreational Fishing Alliance – on top of the thousands in individual donations from The Fisherman readers, regional advertisers, and local fishing clubs – the Northeast Striped Bass Study was poised to deploy up to a half-dozen MiniPSAT devices this past spring. “The plan was to have multiple boats ready to go at one time, with a full Gray FishTag Research team in New York again during the week of May 18,” said Mike Caruso, publisher of The Fisherman and an advisor for Gray FishTag Research, adding “It was going to be even more groundbreaking than in 2019. ”Due to travel restrictions and the shutdown of Wildlife Computers in Washington State where the devices are built, we missed the height of the post-spawn Hudson River bite by roughly two weeks. But thanks to a determined crew at Gray FishTag Research in Florida and a little improvisation, we hit the Jersey Shore spring run off Sandy Hook with a pair of tags, one deployed Thursday, May 28 and another for the following Wednesday, June 3 while fishing with study supporters David Glassberg and Chuck Many aboard Chuck’s boat, Tyman. The pandemic-related audible paid off with a pair of 46-inch plus stripers, appropriately named Cora and Rona.Tag Return #1  With both a MiniPSAT device and a Gray FishTag Research “streamer” tag, a 46-1/2-inch striped bass called Rona is released back in the waters off Sandy Hook for the start of her tracking adventure.So the $10,000 question we’ve all been waiting to answer with baited breath; where did Cora and Rona eventually get to, and did they follow a similar offshore path to what Freedom and Liberty did during the 2019 study? With both a MiniPSAT device and a Gray FishTag Research “streamer” tag, a 46-1/2-inch striped bass called Rona is released back in the waters off Sandy Hook for the start of her tracking adventure.So the $10,000 question we’ve all been waiting to answer with baited breath; where did Cora and Rona eventually get to, and did they follow a similar offshore path to what Freedom and Liberty did during the 2019 study? Once again – just as in 2019 – our first two tag returns of 2020 reveal two coastal stripers taking a rather incredible journey into depths that few would’ve ever expected from striped bass. On August 1, 2020, the Argos satellite first began to receive information from Cora’s tag in roughly 650 feet of water some 30 miles offshore of Gloucester, MA in an area southeast of Jeffreys Ledge along the Murray Basin. According to the information in the MiniPSAT device since uploaded to the satellites, Cora had spent the previous two weeks heading in an easterly direction toward Stellwagen Bank, traveling approximately 85 miles in 14 days from an offshore area home to the Davis and Rodgers basins in the Gulf of Maine. That big striper was along the west side of George’s Bank for the July Fourth weekend, following a bit of meandering above Hydrographer Canyon.As unbelievable as it may be for some us to believe that final month of travel, the route to actually get to George’s Bank was even more shocking. Cora, a 45-3/4-inch striper tagged on June 3, 2020 off Sandy Hook during the spring run, seemingly took a southeast route soon after her release, following a similar path to overseas freighters coming in and out of New York Harbor using the Hudson Canyon to Ambrose Channel deepwater lanes. By June 10, MiniPSAT data shows Cora down past the Chicken Canyon and not far from the Texas Tower, where she would eventually begin tracking northeast towards Nantucket Shoals over a 14-day period before turning north in between Martha’s Vineyard and Nantucket by June 25.For about three weeks, Cora was outside of 3 miles and essentially unavailable to fishing pressure, and her return inshore in late June didn’t last very long either. During the final days of June Cora had cruised back through Nantucket Shoals before running that final offshore gauntlet in July. Anglers along the south shore of Long Island never got a shot at this 35-pounder. We don’t know where she was in the days leading up to her tagging on June 3, nor do we know where she is now, but we have a pretty solid idea about where she was for 53 days this summer, and it wasn’t near the 3-mile-line along the south shore of Long Island.While Cora was the second big striper tagged for the 2020 Northeast Striped Bass Study – sister Rona being first on May 28 in the same stretch of water 2-1/2 miles east of Sandy Hook – her tag was the first to prematurely pop off. According to Bill Dobbelaer, president of Gray FishTag Research, there are any number of reasons why these highly specialized tags may come free. “That fish could’ve gone under a piece of wood and it got hung up and tore loose…the answer is there are endless opportunities for that tag to come off,” Dobbelaer said, adding “it’s more of a miracle that it stays on, and the amount of information that we’ve already gotten from these fish is amazing. Dobbelaer and the Gray FishTag Research team have been involved in countless deployments around the globe with billfish where tags sometimes pop free within days of the initial capture.“It sucks when it comes off two days after we let them go, which happens,” he said.Tag Return #2And then there was Rona. The first of three hefty stripers tagged in 2020 – Independence coming over the July Fourth weekend off Montauk – Rona was also tagged aboard Chuck Many’s Tyman on May 28, and her tag would begin relaying information from roughly 2 miles outside Moriches Inlet off Long Island on August 21. When you look at the chart images of the travels taken by each of these fish, the first thing to understand is that the detailed tracking is not as exact as running on your own onboard GPS. There are quite literally millions of data points collected inside of these MiniPSAT devices bobbing along the Atlantic Ocean somewhere after coming undone from their host. As the Argos satellite passes overhead, the tag transmits its data where it is ultimately gathered by researchers at Gray. The data is then analyzed and input into charts to provide a general idea of migratory paths. “We must always remember that fish in the ocean or wild never swim in a straight line,” said Dobbelaer, explaining “graphs created are averages based upon light sensors, temperature, and depth information.” The graphs are reviewed by the folks at Wildlife Computers in Redmond, WA and the Northeast Striped Bass Study team; at that point, the estimated path of the fish is broken down using the Navionics Boating App with my own Capt. Segull’s charts scattered across the office floor. Essentially, trying to pinpoint a fish’s precise path is like plotting a navigational course.  The first striper deployed with a MiniPSAT device in 2020, Rona shows a rather incredible migratory journey between May 28 and August 15. The first striper deployed with a MiniPSAT device in 2020, Rona shows a rather incredible migratory journey between May 28 and August 15.“They typically transmit for 10 days until the battery dies,” said Roxanne Willmer from Gray FishTag Research explaining how anywhere from 17,000 to 20,000 transmission attempts from the MiniPSAT devices to the overhead satellites once they’ve detached from the fish and floated to the surface. In 2019, both tagging devices were returned after being found on beaches along the Striper Coast, which is what researchers hope happens in 2020 as well. “If we do find them on a beach in three months then we can plug them in, which doesn’t require the battery, and get all of the data, maybe a more defined tracking,” Willmer said. Heading back to the nautical charts with Navionics App in hand, we set to plotting Rona’s course from date of deployment off the Jersey Shore until the tag began to transmit 85 days later. As difficult as it was for any one of us to process – and as hard as it might be for readers to believe – that big fish also traveled southeast along the Hudson Shelf Valley after being tagged, swimming approximately 100 nautical miles to the tip of the Hudson Canyon over the course of just 4 days. “Likelihood” is a common word used in science; based on the best available science, there’s always a probability or chance of something occurring or not occurring in nature, especially when inserting man into the equation. And from the data stored in that MiniPSAT device attached by fishermen into Rona at the beginning of the June, the tracking data showed the likelihood that she was finally on her way towards Moriches Inlet later that month after swimming around the edge of the Hudson and Toms. It would appear that Rona did swim back and forth across the line off Long Island at some point, but data fed to the Argos satellite shows a lot of ground covered over the span of a few weeks before making her northeastern-most stop along Nantucket Shoals by June 25, at roughly the same time as Cora.  While Cora was the second fish “sat” tagged on June 3, hers was the first MiniPSAT to “ping” the Argos satellite on August 1 after coming undone prematurely on July 25.And similar to Cora which traversed darn close to the Texas Tower, data shows Rona making a quick run southwest of the Hudson tip in the area around the Triple Wrecks where yellowfin action was completely off the charts in 2020 with pelagics gorging on sand eels and keeping rods bent through early fall. While Cora was the second fish “sat” tagged on June 3, hers was the first MiniPSAT to “ping” the Argos satellite on August 1 after coming undone prematurely on July 25.And similar to Cora which traversed darn close to the Texas Tower, data shows Rona making a quick run southwest of the Hudson tip in the area around the Triple Wrecks where yellowfin action was completely off the charts in 2020 with pelagics gorging on sand eels and keeping rods bent through early fall. On the move again in a northerly direction, Rona then covers a lot of ground south of Shinnecock at offshore areas during the summer as well, not far from where the Coimbra and Ranger wreck sites were ripe with life in 2020, and at roughly the same time. “What is surprising is the magnitude of the apparent movements of these fish into offshore waters,” said John A. Tiedemann, Assistant Dean in the School of Science at Monmouth University and a longtime striped bass researcher and surfcaster. Tiedemann said he’s gone through 50 years of scientific research without finding any real evidence of such a long range offshore migration; he also noted how there’s never been a satellite tagging effort like this either.“In terms of their range offshore, the striped bass is typically characterized as a nearshore coastal fish and very few life history accounts provide evidence of movements onto the outer continental shelf region,” said Tiedemman, adding “Further analysis of environmental data associated with the movements of these fish may shed light on whether they are moving offshore in response to water temperature, food availability, or simple wanderlust.” Connect The DotsWhere Cora and perhaps a few of her compatriots continued east/northeast, Rona’s satellite tracking shows her cruising back towards Montauk, maintaining an offshore route and crisscrossing her earlier travels until the tag was released somewhere outside of Moriches. Whether she’s still swimming today or was brought to market is anyone’s guess. But as with all of the striped bass fit with MiniPSAT devices, there’s also a green streamer tag affixed to every fish to hopefully gather data on the final stats of each striper tagged. That’s all part of an even bigger effort to get more of the public involved on this collaborative work.  While a global pandemic impacted scheduling of the 2020 Northeast Striped Bass Study, the first batch of tagging gear arrived just in time for the Memorial Day weekend.“It is our team’s mission in our tagging work to always keep the data collected as open access to all,” Dobbelaer said of the team’s research, adding While a global pandemic impacted scheduling of the 2020 Northeast Striped Bass Study, the first batch of tagging gear arrived just in time for the Memorial Day weekend.“It is our team’s mission in our tagging work to always keep the data collected as open access to all,” Dobbelaer said of the team’s research, adding “We will only conclude on the tagged specimen that we are studying, assume nothing of other fish movements or patterns, and continue to look for ways to evolve our own model.”One of those ways is through the use of the green spaghetti tags that have been distributed this season to handful of local charter captains, and which hopefully can be integrated into even more widespread use by anglers in the future science of striped bass. Dobbelaer said that the Gray FishTag Research goal is to expand on their tagging model to gather data from thousands of tagged stripers from the Mid-Atlantic and Northeast, and hopefully using telemetry tagging with a robust spaghetti tag effort to not only track mortality and migration, but to better understand this offshore anomaly.“It is shocking in a short period of time the speed and distance in which these fish traveled. This information is so contrary to what we all have been told,” Dobbelaer said throwing in yet another $10,000 question. “So, what do we do with this astounding information and where do we go from here?”Tiedemman said that although individual striped bass exhibit variable rates of transit, it’s been well established they can move considerable distances in short periods of time. “For example, a fish we acoustically tagged on June 7, 2019 in Sandy Hook Bay was detected off Montauk less than a month later on July 3,” he said, adding “a study published in 2014 documented a striper moving from Delaware Bay to coastal waters off Massachusetts in just 9 days.” Although the number of fish tagged in Northeast Striped Bass Study is still small and thus far only conducted with spring deployments, Tiedemman said it appears to be providing new information on spring and summer movements of larger bass in the region, adding “As the number of satellite tags deployed increases the data yielded by this effort will become more complete and robust.” Again, are we seeing a pattern? Probably too soon to tell, which is why the Northeast Striped Bass Study will continue with support from the fishing community. And on July 3, our team deployed a third MiniPSAT device for 2020 in a 46-inch striper named Independence somewhere between the Porgy Hump and Pollock Rip off Montauk.Furthermore, our team is hoping to be back in action in October for yet another expedition somewhere off Gloucester, MA with Wicked Tuna skipper Dave Marciano in hopes of finding another jumbo to perhaps connect a few more of the striper dots. As of this writing, we again wait with baited breath. READ MORE LIKE THIS AT www.thefisherman.com. |