Using New Technology To Answer An Old Problem…How Old Is That Fish?

Salmon Scale

Figure 1. This is a scale from a 3-year-old landlocked salmon.

By Tyler Grant and Merry Gallagher, Maine DIFW Fisheries Biologists

from The Fishing Wire

One of the more important tasks for fisheries biologists when making management decisions is figuring out how old a fish is. In our last fisheries blog, we discussed how we age fish utilizing fin clips. In this blog, we will focus on two different methods that can be utitlized to age fish.

Fish can vary in age quite substantially from one species to the next. Some species can live to be many decades old whereas others may be fortunate to reach 3 or 4 years. Complicating the matter even further is growth rates of fish can vary tremendously from one waterbody to the next due to variation in environmental conditions and food supply. Comparing fish growth at different ages can give you a good idea of the overall productivity of the system, as well as the overall condition and density of the fish population. In an ideal growth situation like a fish hatchery, a one year old brook trout can reach 8-10″ inches long, while that same one year old fish in the wild may be less than two inches long due to the vastly different growth conditions experienced in the wild. For hatchery fish that have been marked or fin clipped, it is easy to determine a fish’s age because certain fin clips or marks signify a given year that fish was produced or stocked, but for wild fish, it becomes much harder.

Two otoliths

Figure 2. On the right is an otolith taken from a 14” white perch. On the left is an otolith taken from a 40” Northern Pike. Different species have very different sized and shaped otoliths.

For shorter lived species such as brook trout and landlocked salmon, a useful aging method is to age the fish by using it’s scales. Scales are easy to collect and can also be collected without having to kill the fish. Scales grow from the center out and lay down concentric rings like how a tree grows. Tight winter growth rings and wider summer growth rings give you a reasonably accurate method of aging some fishes. However, longer lived species like Lake Trout and Lake Whitefish present a problem. They can easily reach 20 years old and often can be much older and scale aging becomes less reliable for fish species that are slower growing and longer lived. For these fish species, a different method is needed.

Lab equipment for aging fish

Figure 3. The new age lab equipment.

On the right is a sectioning saw with a thin diamond blade for cutting sections of the otolith. On the left is a camera with a microscope lens and a very powerful light for reading and photographing the sectioned otolith. On the computer screen, you can see a sectioned otolith from a Northern Pike.

Otoliths are small bones located at the base of the skull or top of the spinal column in fish, and are commonly used for determining the ages of long lived fishes. Like scales, otoliths have annual growth rings that can be counted to give an estimated age of the fish. However, these bones must be extracted from a dead fish to be used for aging purposes.

Determining the age of a fish from an otolith is still a complicated procedure, and it requires specialized equipment to be done properly. The Maine Department of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife recently acquired the equipment necessary for a Fish Aging Lab that is now located at our Bangor, Maine office.

Lake Trout otolith

Figure 4. A Lake Trout otolith is visible embedded in an epoxy block. The otolith below has been sectioned already and a 0.8 mm slice was taken from the center.

Before the otolith can be sectioned, it must be suspended in a 2-part epoxy within a silicone mold. The epoxy holds the otolith steady so it can be thinly cut by the sectioning saw. This is the most important part. The otoliths are very small, and the first cut must be made precisely or an accurate age cannot be determined. Once the otolith is sliced, the 0.8 mm slice is glued to a microscope slide and sanded and polished to remove the saw marks.

Once the section is prepared, the otolith is magnified under the Aging Lab microscope and by counting the annually-produced rings the biologist can determine the age of the fish. This new technology is already being used to determine the ages of the Lake Trout that were collected in Sebago Lake as part of the Sebago Lake Region’s Summer Profundal Index Netting (SPIN) and it will continue to be a valuable tool for aging long lived fish species, estimating growth rates, and assisting Regional Biologists with valuable age and growth information for their priority populations.

S sectioned otolith

Figure 5. A sectioned otolith glued to a microscope slide and ready to be photographed. The fish number is engraved on the slide for identification purposes. This gives you an idea of the size of an otolith. This microscope slide is 3 inches long.

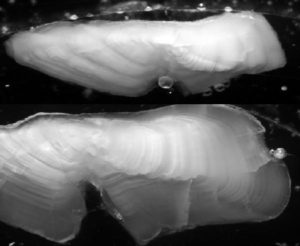

Lake Trout otoliths

Figure 6. Two prepared Lake Trout otoliths. The top fish was 12 inches long and was 4 years old. The bottom fish was 24 inches long and was 17 years old.