“The Five Best Reasons To Pass The Gulf States Plan”

by Jeff Angers

from The Fishing Wire

I’m speaking of the five fish and wildlife management agencies of the Gulf states. I’ve spent the last 20-plus years working with the individuals who lead and work in these departments, and I have found them all to be impressively competent professionals — serious and passionate about sustaining the stocks of fish and game under their management.

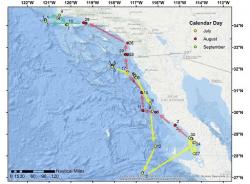

In my own state of Louisiana, we are justly proud of our Department of Wildlife and Fisheries, which has developed a state-of-the-art creel survey for offshore anglers (“LA Creel”).

Now in its third year, the innovative LA Creel survey is providing pinpoint-precise, real-time estimates of fisheries populations and harvest levels.

This is exactly the kind of data that fisheries managers need to protect red snapper — but only if they have the authority to act.

Once Washington gets out of the way, the five state fisheries managers can respond with flexible approaches that reflect the real state of affairs in the Gulf; they will be able to preserve the species for the enjoyment of all sectors, with no group excluded. Today, federal fisheries managers are left to guess — and to play favorites.

It was this kind of advanced knowledge that led Louisiana’s DWF to realize that the recreational red snapper catch during the regular season was short of its quota by at least 88,823 pounds, making possible an extended season that just began November 20. (The extended season will be subject to a daily bag limit of two snapper per person of 16-inch minimum length; Louisiana’s regular state-waters red snapper season ended September 8).

LA Creel is featured in a new video that also introduces us to representatives from all five Gulf state fishery management agencies. It ought to be “Exhibit A” in the case for adopting the five Gulf States’ plan. I urge recreational fishing advocates to watch the video and share it widely on social media.

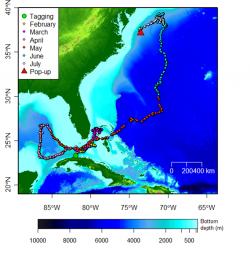

Louisiana isn’t alone: each of the five Gulf States has been at the forefront of advanced fisheries science.

It was their devotion to the sustainability of the red snapper that drove the five states’ fisheries directors to put aside regional, political and personal differences and take the historic step of coming together to develop the five states’ plan.

They were doing what we ask all leaders to do: when confronted with a serious problem like federal mismanagement of the red snapper fishery, real leaders set aside distractions, utilize the most advanced scientific tools and information at their disposal and then act in the best interests of future generations.

It wasn’t just a matter of joining together to fill the vacuum left by the federal government’s mismanagement. The five directors then went further, each of them becoming personally involved in advocating for the plan, both in their own state capitals and in the halls of Congress.

Over the last year, testimony advocating state management from Nick Wiley, the executive director of the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission; Chris Blankenship, the director of the Marine Resources Division of the Alabama Department of Conservation and Natural Resources, and Robert Barham, Secretary of the Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries, before the U.S. House of Representatives has been especially compelling and persuasive.

The state directors traveled to Washington to move the ball forward on their historic agreement. Once H.R.3094 is enacted, their words will be remembered as watershed moments in saving the fish and the fishery.

As those of us who live here know, the Gulf is a very special place, unique in every way. These are the men and women who know it better than anyone else — certainly better than a distant bureaucrat in Washington, D.C., however well intentioned.