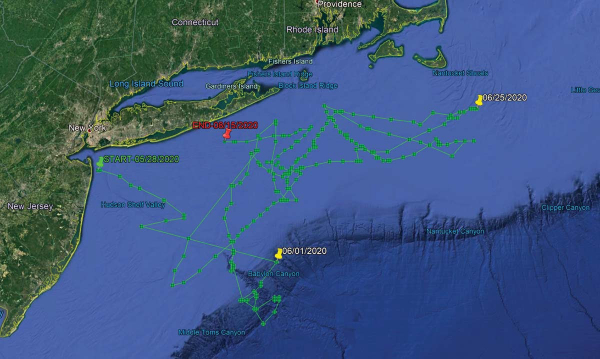

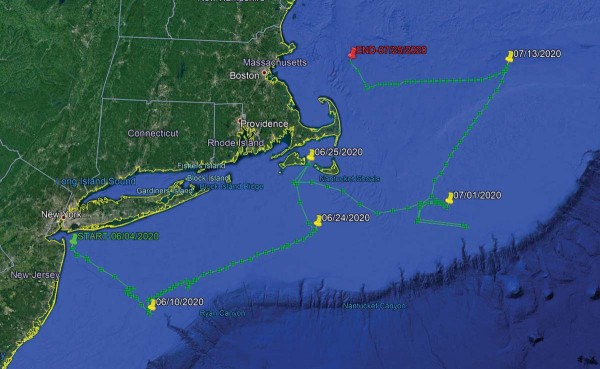

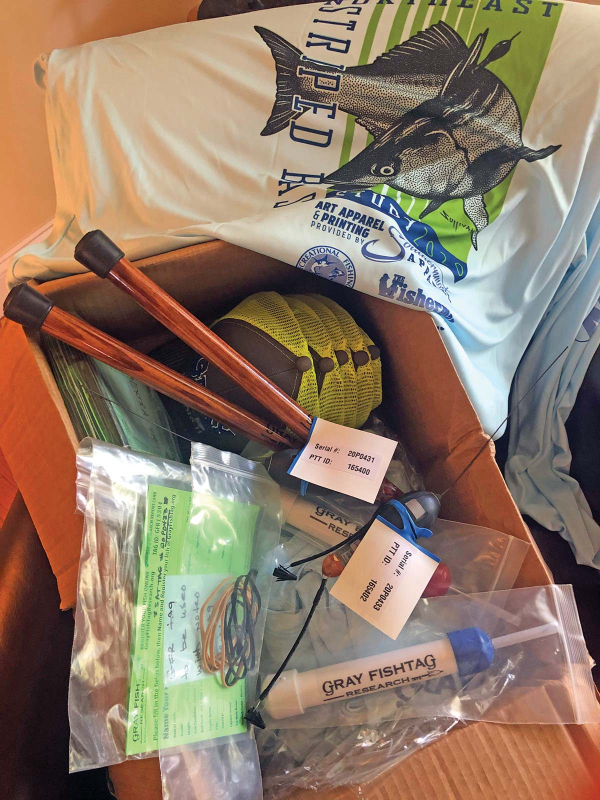

| By Jim Hutchinson, Jr. The Fisherman from The Fishing Wire  Chuck Many nets a good fish for Dave Glassberg during the spring run off the Jersey Shore during the 2020 Northeast Striped Bass Study. Chuck Many nets a good fish for Dave Glassberg during the spring run off the Jersey Shore during the 2020 Northeast Striped Bass Study.And now there are four! “If one’s an anomaly, and two’s a coincidence, will three or more show a pattern?”That was the lead sentence in our first published piece of this year (Born To Run: Hudson River To Canyon Striper) on the status of our 2019 Northeast Striped Bass Study from our January edition. By now everyone along the Striper Coast is aware of the results; two post-spawn striped bass caught by our research team at The Fisherman, Gray FishTag Research and Navionics in May of 2019, tagged with high-tech MiniPSAT devices to track migration habits during a five-month stretch, ultimately showing returns from the offshore canyons including the Hudson, Block and Veatch.Two $5,000 “pop-off” satellite tags which incorporate light-based geolocation for tracking, time-at-depth histograms for measuring diving behavior, and a profile of depth and temperature, showing two very distinct paths in waters where we typically wouldn’t expect striped bass to swim. There’s been some skepticism of course with some questing whether a big white shark gobbled up these stripers before heading east with a belly full of bass. However, the data stored inside the Wildlife Computers MiniPSAT devices – which amazingly were physically recovered by beachcombers in Massachusetts and New Jersey – shows both tagged fish were alive and swimming along the offshore grounds when the tags detached.We had grand plans in 2020, and with financial support from Navionics, Tsunami Tackle, AFW/HiSeas, Southernmost Apparel and the Recreational Fishing Alliance – on top of the thousands in individual donations from The Fisherman readers, regional advertisers, and local fishing clubs – the Northeast Striped Bass Study was poised to deploy up to a half-dozen MiniPSAT devices this past spring. “The plan was to have multiple boats ready to go at one time, with a full Gray FishTag Research team in New York again during the week of May 18,” said Mike Caruso, publisher of The Fisherman and an advisor for Gray FishTag Research, adding “It was going to be even more groundbreaking than in 2019. ”Due to travel restrictions and the shutdown of Wildlife Computers in Washington State where the devices are built, we missed the height of the post-spawn Hudson River bite by roughly two weeks. But thanks to a determined crew at Gray FishTag Research in Florida and a little improvisation, we hit the Jersey Shore spring run off Sandy Hook with a pair of tags, one deployed Thursday, May 28 and another for the following Wednesday, June 3 while fishing with study supporters David Glassberg and Chuck Many aboard Chuck’s boat, Tyman. The pandemic-related audible paid off with a pair of 46-inch plus stripers, appropriately named Cora and Rona.Tag Return #1  With both a MiniPSAT device and a Gray FishTag Research “streamer” tag, a 46-1/2-inch striped bass called Rona is released back in the waters off Sandy Hook for the start of her tracking adventure.So the $10,000 question we’ve all been waiting to answer with baited breath; where did Cora and Rona eventually get to, and did they follow a similar offshore path to what Freedom and Liberty did during the 2019 study? With both a MiniPSAT device and a Gray FishTag Research “streamer” tag, a 46-1/2-inch striped bass called Rona is released back in the waters off Sandy Hook for the start of her tracking adventure.So the $10,000 question we’ve all been waiting to answer with baited breath; where did Cora and Rona eventually get to, and did they follow a similar offshore path to what Freedom and Liberty did during the 2019 study? Once again – just as in 2019 – our first two tag returns of 2020 reveal two coastal stripers taking a rather incredible journey into depths that few would’ve ever expected from striped bass. On August 1, 2020, the Argos satellite first began to receive information from Cora’s tag in roughly 650 feet of water some 30 miles offshore of Gloucester, MA in an area southeast of Jeffreys Ledge along the Murray Basin. According to the information in the MiniPSAT device since uploaded to the satellites, Cora had spent the previous two weeks heading in an easterly direction toward Stellwagen Bank, traveling approximately 85 miles in 14 days from an offshore area home to the Davis and Rodgers basins in the Gulf of Maine. That big striper was along the west side of George’s Bank for the July Fourth weekend, following a bit of meandering above Hydrographer Canyon.As unbelievable as it may be for some us to believe that final month of travel, the route to actually get to George’s Bank was even more shocking. Cora, a 45-3/4-inch striper tagged on June 3, 2020 off Sandy Hook during the spring run, seemingly took a southeast route soon after her release, following a similar path to overseas freighters coming in and out of New York Harbor using the Hudson Canyon to Ambrose Channel deepwater lanes. By June 10, MiniPSAT data shows Cora down past the Chicken Canyon and not far from the Texas Tower, where she would eventually begin tracking northeast towards Nantucket Shoals over a 14-day period before turning north in between Martha’s Vineyard and Nantucket by June 25.For about three weeks, Cora was outside of 3 miles and essentially unavailable to fishing pressure, and her return inshore in late June didn’t last very long either. During the final days of June Cora had cruised back through Nantucket Shoals before running that final offshore gauntlet in July. Anglers along the south shore of Long Island never got a shot at this 35-pounder. We don’t know where she was in the days leading up to her tagging on June 3, nor do we know where she is now, but we have a pretty solid idea about where she was for 53 days this summer, and it wasn’t near the 3-mile-line along the south shore of Long Island.While Cora was the second big striper tagged for the 2020 Northeast Striped Bass Study – sister Rona being first on May 28 in the same stretch of water 2-1/2 miles east of Sandy Hook – her tag was the first to prematurely pop off. According to Bill Dobbelaer, president of Gray FishTag Research, there are any number of reasons why these highly specialized tags may come free. “That fish could’ve gone under a piece of wood and it got hung up and tore loose…the answer is there are endless opportunities for that tag to come off,” Dobbelaer said, adding “it’s more of a miracle that it stays on, and the amount of information that we’ve already gotten from these fish is amazing. Dobbelaer and the Gray FishTag Research team have been involved in countless deployments around the globe with billfish where tags sometimes pop free within days of the initial capture.“It sucks when it comes off two days after we let them go, which happens,” he said.Tag Return #2And then there was Rona. The first of three hefty stripers tagged in 2020 – Independence coming over the July Fourth weekend off Montauk – Rona was also tagged aboard Chuck Many’s Tyman on May 28, and her tag would begin relaying information from roughly 2 miles outside Moriches Inlet off Long Island on August 21. When you look at the chart images of the travels taken by each of these fish, the first thing to understand is that the detailed tracking is not as exact as running on your own onboard GPS. There are quite literally millions of data points collected inside of these MiniPSAT devices bobbing along the Atlantic Ocean somewhere after coming undone from their host. As the Argos satellite passes overhead, the tag transmits its data where it is ultimately gathered by researchers at Gray. The data is then analyzed and input into charts to provide a general idea of migratory paths. “We must always remember that fish in the ocean or wild never swim in a straight line,” said Dobbelaer, explaining “graphs created are averages based upon light sensors, temperature, and depth information.” The graphs are reviewed by the folks at Wildlife Computers in Redmond, WA and the Northeast Striped Bass Study team; at that point, the estimated path of the fish is broken down using the Navionics Boating App with my own Capt. Segull’s charts scattered across the office floor. Essentially, trying to pinpoint a fish’s precise path is like plotting a navigational course.  The first striper deployed with a MiniPSAT device in 2020, Rona shows a rather incredible migratory journey between May 28 and August 15. The first striper deployed with a MiniPSAT device in 2020, Rona shows a rather incredible migratory journey between May 28 and August 15.“They typically transmit for 10 days until the battery dies,” said Roxanne Willmer from Gray FishTag Research explaining how anywhere from 17,000 to 20,000 transmission attempts from the MiniPSAT devices to the overhead satellites once they’ve detached from the fish and floated to the surface. In 2019, both tagging devices were returned after being found on beaches along the Striper Coast, which is what researchers hope happens in 2020 as well. “If we do find them on a beach in three months then we can plug them in, which doesn’t require the battery, and get all of the data, maybe a more defined tracking,” Willmer said. Heading back to the nautical charts with Navionics App in hand, we set to plotting Rona’s course from date of deployment off the Jersey Shore until the tag began to transmit 85 days later. As difficult as it was for any one of us to process – and as hard as it might be for readers to believe – that big fish also traveled southeast along the Hudson Shelf Valley after being tagged, swimming approximately 100 nautical miles to the tip of the Hudson Canyon over the course of just 4 days. “Likelihood” is a common word used in science; based on the best available science, there’s always a probability or chance of something occurring or not occurring in nature, especially when inserting man into the equation. And from the data stored in that MiniPSAT device attached by fishermen into Rona at the beginning of the June, the tracking data showed the likelihood that she was finally on her way towards Moriches Inlet later that month after swimming around the edge of the Hudson and Toms. It would appear that Rona did swim back and forth across the line off Long Island at some point, but data fed to the Argos satellite shows a lot of ground covered over the span of a few weeks before making her northeastern-most stop along Nantucket Shoals by June 25, at roughly the same time as Cora.  While Cora was the second fish “sat” tagged on June 3, hers was the first MiniPSAT to “ping” the Argos satellite on August 1 after coming undone prematurely on July 25.And similar to Cora which traversed darn close to the Texas Tower, data shows Rona making a quick run southwest of the Hudson tip in the area around the Triple Wrecks where yellowfin action was completely off the charts in 2020 with pelagics gorging on sand eels and keeping rods bent through early fall. While Cora was the second fish “sat” tagged on June 3, hers was the first MiniPSAT to “ping” the Argos satellite on August 1 after coming undone prematurely on July 25.And similar to Cora which traversed darn close to the Texas Tower, data shows Rona making a quick run southwest of the Hudson tip in the area around the Triple Wrecks where yellowfin action was completely off the charts in 2020 with pelagics gorging on sand eels and keeping rods bent through early fall. On the move again in a northerly direction, Rona then covers a lot of ground south of Shinnecock at offshore areas during the summer as well, not far from where the Coimbra and Ranger wreck sites were ripe with life in 2020, and at roughly the same time. “What is surprising is the magnitude of the apparent movements of these fish into offshore waters,” said John A. Tiedemann, Assistant Dean in the School of Science at Monmouth University and a longtime striped bass researcher and surfcaster. Tiedemann said he’s gone through 50 years of scientific research without finding any real evidence of such a long range offshore migration; he also noted how there’s never been a satellite tagging effort like this either.“In terms of their range offshore, the striped bass is typically characterized as a nearshore coastal fish and very few life history accounts provide evidence of movements onto the outer continental shelf region,” said Tiedemman, adding “Further analysis of environmental data associated with the movements of these fish may shed light on whether they are moving offshore in response to water temperature, food availability, or simple wanderlust.” Connect The DotsWhere Cora and perhaps a few of her compatriots continued east/northeast, Rona’s satellite tracking shows her cruising back towards Montauk, maintaining an offshore route and crisscrossing her earlier travels until the tag was released somewhere outside of Moriches. Whether she’s still swimming today or was brought to market is anyone’s guess. But as with all of the striped bass fit with MiniPSAT devices, there’s also a green streamer tag affixed to every fish to hopefully gather data on the final stats of each striper tagged. That’s all part of an even bigger effort to get more of the public involved on this collaborative work.  While a global pandemic impacted scheduling of the 2020 Northeast Striped Bass Study, the first batch of tagging gear arrived just in time for the Memorial Day weekend.“It is our team’s mission in our tagging work to always keep the data collected as open access to all,” Dobbelaer said of the team’s research, adding While a global pandemic impacted scheduling of the 2020 Northeast Striped Bass Study, the first batch of tagging gear arrived just in time for the Memorial Day weekend.“It is our team’s mission in our tagging work to always keep the data collected as open access to all,” Dobbelaer said of the team’s research, adding “We will only conclude on the tagged specimen that we are studying, assume nothing of other fish movements or patterns, and continue to look for ways to evolve our own model.”One of those ways is through the use of the green spaghetti tags that have been distributed this season to handful of local charter captains, and which hopefully can be integrated into even more widespread use by anglers in the future science of striped bass. Dobbelaer said that the Gray FishTag Research goal is to expand on their tagging model to gather data from thousands of tagged stripers from the Mid-Atlantic and Northeast, and hopefully using telemetry tagging with a robust spaghetti tag effort to not only track mortality and migration, but to better understand this offshore anomaly.“It is shocking in a short period of time the speed and distance in which these fish traveled. This information is so contrary to what we all have been told,” Dobbelaer said throwing in yet another $10,000 question. “So, what do we do with this astounding information and where do we go from here?”Tiedemman said that although individual striped bass exhibit variable rates of transit, it’s been well established they can move considerable distances in short periods of time. “For example, a fish we acoustically tagged on June 7, 2019 in Sandy Hook Bay was detected off Montauk less than a month later on July 3,” he said, adding “a study published in 2014 documented a striper moving from Delaware Bay to coastal waters off Massachusetts in just 9 days.” Although the number of fish tagged in Northeast Striped Bass Study is still small and thus far only conducted with spring deployments, Tiedemman said it appears to be providing new information on spring and summer movements of larger bass in the region, adding “As the number of satellite tags deployed increases the data yielded by this effort will become more complete and robust.” Again, are we seeing a pattern? Probably too soon to tell, which is why the Northeast Striped Bass Study will continue with support from the fishing community. And on July 3, our team deployed a third MiniPSAT device for 2020 in a 46-inch striper named Independence somewhere between the Porgy Hump and Pollock Rip off Montauk.Furthermore, our team is hoping to be back in action in October for yet another expedition somewhere off Gloucester, MA with Wicked Tuna skipper Dave Marciano in hopes of finding another jumbo to perhaps connect a few more of the striper dots. As of this writing, we again wait with baited breath. READ MORE LIKE THIS AT www.thefisherman.com. |

Category Archives: Conservation

Dams and Atlantic Salmon

| New modelling helps scientists explore what happens when endangered Atlantic salmon have access to more of their habitat. From NOAA Fisheries from The Fishing Wire  Weldon Dam on the Penobscot River in Maine. Weldon Dam on the Penobscot River in Maine. Photo courtesy Brookfield Renewable PowerNOAA Fisheries Atlantic salmon researchers have found that Atlantic salmon abundance can increase as more young fish and returning adults survive their encounters with dams. Also, progress in rebuilding the population will depend heavily on continuing stocking of hatchery fish raised especially for this purpose. This information is based on a life history model and new information on changes in the Penobscot River watershed. The remaining remnant Atlantic salmon populations in the United States are located in Maine, with the largest population in the Penobscot River. Numerous factors play a role in salmon recovery — from predation and habitat degradation to pollution and climate change. The two most influential factors are survival of fish as they navigate dams in the river, and survival during the marine phase of their life. Atlantic salmon are born and remain in fresh water for 1-3 years and migrate downriver through estuaries into the sea. Then they spend 1 to 2 years at sea before returning to the river where they were born to spawn.  Hatchery salmon smolt Hatchery salmon smolt“Our findings indicate that Atlantic salmon abundance can increase as survival at dams from the lower to the upper watershed increases. Hatchery supplementation will be necessary to sustain the population when survival is low in egg-to-smolt and marine life stages,” said Julie Nieland, a salmon researcher at the science center’s Woods Hole Laboratory in Massachusetts and lead author of the study. “Increases in survival during both of these life stages will likely be necessary to attain a self-sustaining population, especially if hatchery supplementation is reduced or discontinued. ”Updating What We know About Salmon Survival Nieland and center colleague Tim Sheehan used an existing dam impact analysis model to look at how survival at dams, increased survival at key life stages, and hatchery supplementation affected the Atlantic salmon population. The model was developed in 2012 and first used in federal licensing analyses for five hydroelectric dams in the Penobscot River. Nieland and Sheehan updated the model, adding new data and better accounting for changes in the watershed. They ran different scenarios to assess the effects of changing smolt numbers, stocking locations, and increasing survival in the egg-to-smolt and marine life stages. They also looked at scenarios involving various dams to estimate abundance and distribution of Atlantic salmon within the watershed and at different life stages. This included the smolt and adult stages when salmon encounter dams. Analyzing an Upstream Dam  Fish passage at Weldon Dam on the Penobscot River in Maine Fish passage at Weldon Dam on the Penobscot River in MaineThe study focused on Weldon Dam in Mattawamkeag, about 65 miles upstream from Bangor, Maine. The dam is the fifth and farthest upstream dam on the main stem of the Penobscot. It is currently undergoing relicensing by the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission as part of the Mattaceunk Project. There are a large number of dams in the Penobscot watershed. A better understanding of how dams alter important ecological function for salmon has proven to be a key advance in managing salmon recovery. For example, moving stocking locations lower in the watershed helped maximize adult return rates. Habitat Access Critical to Salmon Recovery The current stocking strategy minimizes Atlantic salmon deaths from dams. However, the population of Atlantic salmon is currently found in the lower watershed where habitat is lower quality. Increased survival and passage at dams will allow salmon to access the upper watershed where there is higher quality habitat. Habitat quality could be an important piece of the puzzle for Atlantic salmon. Higher quality habitat would likely produce more smolts than lower quality habitat, but the potential benefits of increased habitat quality are not yet quantifiable.  Viewing box at a dam fish passage as salmon migrate upstream . Viewing box at a dam fish passage as salmon migrate upstream .The authors suggest that future research should focus on measuring the biological response of Atlantic salmon to different habitat qualities and evaluating the effects of changing habitat conditions on Atlantic salmon productivity. This would allow researchers to identify areas where salmon would thrive and quantify how a changing climate affects productivity. These results will also pave the way for a data-driven assessment of future productivity for U.S. Atlantic salmon. Managers will then be able to develop realistic recovery goals while prioritizing restoration efforts in areas with the greatest potential future productivity. In addition to Atlantic salmon, populations of American shad, blueback herring, alewife and American eel in the Penobscot watershed could also benefit from increased dam passage and dam removal. Better passage and survival at dams would also allow these species to access higher quality habitat further up in the river. For more information, please contact Shelley Dawicki. |

Keep Some Small Bass To Eat

Harvest of lots of small bass can mean more “slot” fish in the future in some overpopulated lakes like Arkansas’ Lake Brewer and others. from The Fishing Wire PLUMMERVILLE — A winning weight of 10 fish for just over 10 pounds would have most bass-fishing tournament directors contemplating a permanent blacklisting of the lake from their schedule, but Jared Pridmore, director of the Lake Brewer Bass Club and owner of JP Custom Baits in Arkansas, was nothing but smiles when he saw the results of his “Tiny Fish Tournament” in April. The only thing that made him happier than the low weight was the sight of the fish-filled cooler where participants turned in their fish instead of releasing them to the water. Lake Brewer is the main drinking water supply for about 20,000 people in Conway County as well as another 60,000 people in and around the City of Conway in Faulkner County. It was constructed in 1983 by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and maintenance of the lake was turned over to the Conway Corporation the year it was built. In addition to providing water for nearby residents, the 1,166-acre reservoir has proven to be a fantastic fishery, even being featured in an episode of Major League Fishing a few years ago. “Brewer is a great lake, and about five years ago, you needed to have at least five fish for 20 pounds to have a chance of placing in a tournament there, but it’s getting full of small fish,” Pridmore said. “Word got out that it was hot, and between fishing pressure and the tons of small fish, you don’t see nearly as many fish over the lake’s slot limit.” The “slot limit” Pridmore refers to is a special regulation placed on some lakes where bass of a certain size must be released immediately back to the water to protect them from harvest. In Brewer’s case, any largemouth bass between 13 and 16 inches long cannot be kept for eating or weigh-ins to be released later, but fish under 13 inches and over 16 inches can be kept. According to Matt Schroeder, fisheries biologist at the Arkansas Game and Fish Commission’s Mayflower office, slot limits are intended to help produce and maintain good fish populations, but can have a negative effect if some harvest isn’t practiced. “Lakes that have good growth and produce consistently good spawns are typical candidates for slot limits,” Schroeder said. “You’re wanting to protect your best spawning year classes of fish, while allowing harvest above and below that to thin out some of the competition for food. Your most abundant year-class of fish is going to be the youngest fish, so harvesting them lets the fish in the protected slot get more food and grow to larger sizes.” But Schroeder warns that if no one is harvesting the small fish, the slot limit becomes ineffective and the lake may see slower growth from too many mouths to feed. “You’ve essentially created a minimum length limit at that point, and lakes with good recruitment and good growth can actually see a decline in production of large fish when that happens,” Schroeder said. “We want people catching and keeping the fish under the slot limit if it’s going to work.” Pridmore, and Lake Brewer Bass Club president Lynn Hensley say they want to do what they can to help bring bigger fish back to the lake. “You catch a ton of those small fish in here right now,” Hensley said. “And you’re not going to get big fish if all the food is going to those small ones.” The April tiny fish tournament had some major differences from standard fishing tournaments: Anglers could weigh in up to 10 largemouth bass per boat that were under the 13- to 16-inch slot limit. All largemouth bass weighed that were under the slot were put in a cooler for any of the anglers to take home and enjoy as long as they didn’t go over any possession limits. Even with the catch-and-keep rules in place, tournament directors still released a few fish. “We let every team weigh in one fish that was over the slot limit in a separate big-fish contest, so anyone who caught a big one today would still get to enjoy a shot at a prize,” said Lynn Hensley, club president. “We released all fish over the slot back to the water. We also released any Kentucky bass because they aren’t included in the slot limit regulations.” Overall, the tournament was a success, and many of the anglers still had the same competitive spirit at weigh-in, although social distancing protocols in April prevented any large crowds at the weigh-in table. At the end of the day, the team of Luci and Chris Johnson from Prairie Grove took the title with 10 fish weighing a less than massive 10.35 pounds. “We had 22 teams show up to fish, which isn’t bad considering the social distancing that we all have to work through,” Pridmore said. “We even had folks like [the Johnsons] who drive down from Northwest Arkansas to join in the fun. We pulled a little over 100 fish under the slot limit from the lake.” While 100 fish being removed isn’t likely to influence the growth rates of fish in a lake as large and fertile as Brewer, Ben Batten, AGFC chief of fisheries, says it’s more about promoting the principle that keeping fish is OK, and even needed in some cases. “There are a lot more bass swimming in that lake than most anglers realize,” Batten said. “We don’t manage these lakes for fish to die of old age. Bass are a renewable resource, and we manage the lakes so people can enjoy fishing for them. Some people don’t want to keep any fish, and that’s fine, but others do want to catch and keep, and that’s totally fine, too. We set limits to make sure the resource remains and we factor harvest into that decision.” |

Great American Outdoors Act Going to the President

| President Trump signed it after this was posted. |

| Jim Shepherd from The Fishing Wire “We’re pretty confident we easily have the votes,” one outdoor organization’s CEO told me, adding, “it’s curious that it’s mostly western Republicans who don’t like the LWCF. Gulf States members – again primarily R’s- don’t think they get enough of a local deal since the money comes from offshore oil and gas, the fiscal conservatives will all vote no.” To me that conversation didn’t sound negative, but it was a realistic view of what should and did happen. Shortly after our conversation, the U.S. House of Representatives voted overwhelmingly (310 to 107) to finally approve the Great American Outdoors Act. Passage means that after ten years of work, President Trump’s signature is all that lies between the continued decline of our national public lands and the allocation of sufficient federal funds to repair most of the critically shaky infrastructure that supports those precious public lands. Technically, H.R. 7092 “establishes the National Parks and Public Land Legacy Restoration Fund to support deferred maintenance projects on federal lands.”It also makes funding for the Land and Water Conservation Fund (LWCF) permanent. The net/net is that the National Park Service, the Forest Service, Fish and Wildlife Service, Bureau of Land Management and Bureau of Indian Education will get the funding for projects that have been deferred due to a shortage of funds. As I’ve written before, it required ten years of legislative work by conservation groups, and represents a huge step toward taking care of our public lands going forward.In fact, I’ve learned that before some pretty strong lobbying President Trump was set to strip virtually all funding from the LWCF. That was before he met with conservation leaders and Congressional proponents. They were successful in showing him the measure wasn’t just important, it was crucial. In response, the President tweeted this on March 3: “I am calling on Congress to send me a Bill that fully and permanently funds the LWCF and restores our National Parks. When I sign it into law it will be HISTORIC for all our beautiful public lands.”He’s not the slightest bit disinclined to sign the bill. And that is one tweet that’s not any overstatement. Permanent funding means managers can finally create workable budgets, based on the assumption that the monies will be there. In praising the passage, Interior Secretary David Bernhardt said “In March, President Trump called on Congress to stop kicking the can down the road, fix the aging infrastructure at our national parks and permanently fund conservation projects through the Land and Water Conservation Fund. He accomplished what previous Presidents have failed to do for decades, despite their lip service commitment to funding public land improvements.” It is truly one of the most non-partisan measures to pass Congress in some time. Last year, the National Park Service had 327 million visitors. They generated an economic impact estimated at $41 billion dollars. That supported 340,000 jobs. Granted, COVID-19 severely reduced visitation for the past few months, but as we all realize, the outdoors remains one of the safest options for everything from recreation to solitude. Soon, the more than 5,500 miles of paved roads, 17,000 miles of trails and 24,000 buildings that comprise our National Parks can get some much-needed repair, making them even more alluring -and safe- for visitors. And as the National Park traffic increases, businesses nearby see increases in traffic as well. It’s an economic engine that benefits everyone. But we all know being outside cures a lot of the problems with our insides, don’t we? We’ll keep you posted. |

Submerged Aquatic Vegetation

| NOAA Fisheries reminds us that submerged aquatic vegetation is one of the most productive fish habitats on earth. Imagine this: you’re swimming at your favorite beach and you feel something slide across your foot. You panic, but only for a moment, because you realize that what you were touching was just a long, spindly water plant. Sure, you may have seen such plants washed up on beaches, or maybe you have removed it from a boat as you left the water for the day. But have you ever stopped to think about what these plants actually do? It turns out, they actually support an entire ecosystem under the water! The term used for a rooted aquatic plant that grows completely under water is submerged aquatic vegetation (SAV). These plants occur in both freshwater and saltwater but in estuaries, where fresh and saltwater mix together, they can be an especially important habitat for fish, crabs, and other aquatic organisms. SAV is a great habitat for fish, including commercially important species, because it provides them with a place to hide from predators and it hosts a buffet of small invertebrates and other prey. They essentially form a canopy, much like that of a forest but underwater. Burrowing organisms, like clams and worms, live in the sediments among the roots, while fish and crabs hide among the shoots and leaves, and ducks graze from above. It has been estimated that a single acre of SAV can be home to as many as 40,000 fish and 50 million small invertebrates!  SAV in the Chesapeake Bay. Credit: Maryland Department of Natural Resources SAV in the Chesapeake Bay. Credit: Maryland Department of Natural ResourcesSAV in the Chesapeake BayOne of the places we work to protect these aquatic plants—and other habitats important for fish)—is in the Chesapeake Bay (Maryland and Virginia). The Bay is home to several different species of SAV. They live in the relatively freshwaters near the head of the Bay and down to its mouth, which is as salty as the ocean. Approximately 90 percent of the historical extent of SAV disappeared around the mid-20th century due to poor water quality, coastal development activities, and disease. Since then, there have been major efforts to reduce pollution to the bay and help SAV reestablishin areas where it was historically found. We regularly work with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to ensure that coastal projects avoid damaging this important habitat. For example, the Corps might propose to issue a permit to a private landowner to build a structure such as a pier or breakwater in SAV. We would then make recommendations to avoid these areas. If the areas are unavoidable, we advocate for different construction approaches to minimize impacts such as shading or filling.Dead Zones Giving You Heartburn? Have an Antacid!One amazing recent finding is that SAV actually changes the acidity of near-shore waters. A recent study in the journal Naturedescribes this phenomenon in the Chesapeake Bay. SAV located at the head of the bay reduces the acidity of water in areas downstream. Areas of low oxygen form when carbon dioxide gas is released by fish, bacteria, and other aquatic organisms. As they respire, or breathe, they take up oxygen and release carbon dioxide as part of normal biological operation. These “dead zones” are areas with oxygen levels below what is necessary to support fish, shellfish, and other aquatic life.During the warm summer months in the Chesapeake Bay, there are many aquatic organisms respiring. This results in much of the available oxygen being consumed and leaving an excess of dissolved carbon dioxide. Another effect of all this carbon dioxide is that parts of the Bay become more acidic. This is stressful for many organisms especially those with shells like oysters and mussels. That’s where SAV comes in. During the growing season, SAV absorbs dissolved carbon dioxide. With help from the sun’s rays, they turn that carbon into leaves, shoots, and roots much like other plants. In the process, oxygen is released into the water, as well as small crystals of calcium carbonate. They essentially behave as antacids as they flow into acidic waters downstream. This is a great example of how conservation of one resource can have cascading effects. SAV carbon filtration benefits commercial fisheries such as oyster aquaculture and, ultimately, the entire Chesapeake Bay ecosystem.  SAV growing in shallow water near Havre de Grace, MD. Credit: Will Parson/Chesapeake Bay Program SAV growing in shallow water near Havre de Grace, MD. Credit: Will Parson/Chesapeake Bay ProgramSAV as a Carbon SpongeIncreasing carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere is also a major contributing factor in global climate change. There is a lot of interest in harnessing the power of our natural biological environment to soak up this excess carbon. SAV is an important piece in this puzzle. Aquatic plants are highly productive, which means they absorb a lot of carbon dioxide. The carbon captured by these plants has been termed “blue carbon” since it primarily occurs in the water. Blue carbon has been receiving a lot of attention lately as scientists have discovered that aquatic plants are very efficient at storing carbon in sediments. They also keep it there over long periods of time. Studies have estimated that underwater grasses globally can store approximately 10 percent of the carbon in the entire ocean in the form of rich aquatic soils. Ultimately, this means that efforts to protect and restore SAV can also help to reduce the effects of climate change. Take a Second Look at SAVMaybe next time you feel a spindly plant brush your foot in the water, you won’t run away. Instead, dive down and see what critters may be hiding among the underwater grasses! You might be surprised to find a crab lumbering through the stems or school of young fish cruising through the green leaves. |

Measuring Atlantic Bluefin Tuna With a Drone

| Measuring Bluefin Tuna This novel use of drones is a promising way to remotely monitor these hard-to-see fish. From NOAA Fisheries from The Fishing Wire Researchers have used an unmanned aerial system (or drone) to gather data on schooling juvenile Atlantic bluefin tuna in the Gulf of Maine. This pilot study tested whether a drone could keep up with the tuna while also taking photographs that captured physical details of this fast-moving fish. The drone was equipped with a high-resolution digital still image camera. Results show that drones can capture images of both individual fish and schools. They may be a useful tool for remotely monitoring behavior and body conditions of the elusive fish. Individual fish lengths and widths, and the distance between fish near the sea surface, were measured to less than a centimeter of precision. We used an APH-22, a battery-powered, six-rotor drone. The pilot study was conducted in the Atlantic bluefin tuna’s foraging grounds northeast of Cape Cod in the southern Gulf of Maine.Mike Jech about to launch the APH-22 from the bow of the F/V Lily. Photo @2015 Eric Schwartz.“Multi-rotor unmanned aerial systems won’t replace shipboard surveys or the reliance on manned aircraft to cover a large area,” said Mike Jech, an acoustics researcher at the Northeast Fisheries Science Center in Woods Hole, Massachusetts and lead author of the study. “They have a limited flight range due to battery power and can only collect data in bursts. Despite some limitations, they will be invaluable for collecting remote high-resolution images that can provide data at the accuracy and precision needed by managers for growth and ecosystem models of Atlantic bluefin tuna.”Results from the APH-22 study were published in March 2020 in theJournal of Unmanned Vehicle Systems. Researchers conducted their work in 2015. They then compared their study results to values in published data collected in the same general area. They also compared it to recreational landings data collected through NOAA Fisheries’ Marine Recreational Information Program. Taking up the Bluefin Tuna Sampling ChallengeAtlantic bluefin tuna is a commercially and ecologically important fish. The population size in the western Atlantic Ocean is unknown. Fishery managers need biological data about this population, but it is hard to get. Highly migratory species like Atlantic bluefin tuna often move faster than the vessels trying to sample them. The tuna are distributed across large areas, and can be found from the sea surface to hundreds of feet deep. Sampling with traditional gear — nets and trawls — is ineffective. Acoustical methods are useful but limited to sampling directly below a seagoing vessel with echosounders or within range of horizontal sonar. It is also difficult to estimate the number of tuna in a school from an airplane. Both fish availability and perception biases introduced by observers can affect results. Estimates of abundance and size of individuals within a school are hard to independently verify. Taking precision measurements of animals that are in constant motion near the surface proved easier with a drone that is lightweight, portable, and agile in flight. It can carry a high-quality digital still camera, and be deployed quickly from a small fishing boat. Short flight times limit a drone’s ability to survey large areas. However, they can provide two-dimensional images of the shape of a fish school and data to count specific individuals just below the ocean surface.New Capacity for Bluefin Tuna Monitoring The APH-22 system has been tested and evaluated for measuring other marine animals. It’s been used in a number of environments — from Antarctica to the Pacific Ocean — prior to its use in the northwest Atlantic Ocean. Previous studies estimated the abundance and size of penguins and leopard seals, and the size and identity of individual killer whales. Hexacopter image of a school of Atlantic bluefin tuna taken northeast of Provincetown, Massachusetts in the southern Gulf of Maine. “The platform is ideal for accurately measuring fish length, width, and the distance between individuals in a school when you apply calibration settings and performance measures,” Jech said. “We were able to locate the hexacopter in three-dimensional space and monitor its orientation to obtain images with a resolution that allowed us to make measurements of individual fish.” As new unmanned aerial systems are developed, their use to remotely survey Atlantic bluefin tuna and other animals at the sea surface will evolve. It may minimize the reliance on manned aircraft or supplement shipboard surveys. The International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas governs tuna fishing. It is entrusted to monitor and manage tuna and tuna-like species in the Atlantic Ocean and adjacent seas. NOAA Fisheries manages the Atlantic bluefin tuna fishery in the United States. We set regulations for the U.S. fishery based on conservation and management recommendations from the international commission. For more information, contact Shelley Dawicki |

NOAA Fisheries Now More Responsive to Needs of Recreational Anglers

| Russ Dunn from The Fishing Wire Read a new leadership message from Russ Dunn, National Policy Advisor for Recreational Fisheries, in honor of National Fishing and Boating Week. Anglers motoring a boat in California’s Sacramento Delta at sunrise. Photo: NOAA Fisheries/Jeremy NotchMore than 10 years ago, NOAA officially launched the National Recreational Fisheries Initiative with the opening of the National Saltwater Recreational Fisheries Summit on April 16-17, 2010. Days prior to the Summit, ESPN published a column musing about the demise of recreational fishing as we knew it. The Deepwater Horizon oil rig exploded just three days later. Bookended by these events, the first national Summit opened a challenging long-term dialogue. It produced a very clear message: marine recreational fishermen had long-held frustrations with federal fisheries management they wanted addressed. We left that first Summit understanding the need for institutional change, active public engagement, and the value of public-private partnerships. And we responded by changing the way we thought about recreational fisheries from top to bottom. We expanded agency planning, focus, and accountability around recreational fisheries through a series of detailed regional and national action plans between 2010 and 2019. And, we codified our new approach in the groundbreaking Saltwater Recreational Fisheries Policy in 2014. Since 2010, active engagement and partnership with the recreational community has become deeply ingrained in agency culture. From quadrennial national summits to annual roundtable discussions in every part of the country, the agency works to stay current and connected. We have funded recreational fishermen to research and address many on-the-water priorities such as barotrauma and release mortality, marine debris, habitat restoration, and fish migration. We are working to educate the next generation of anglers, captains, and guides. We accomplish this by supporting programs as varied as the Marine Resource Education Program and the Bristol Bay Fly Fishing Academy. In 2019, we reached another milestone when we signed a formal Memorandum of Agreement with leading recreational fishing community members at the Miami Boat Show. The MOA established a formal framework for communication and collaboration on mutually beneficial projects. They will advance our goals of supporting and promoting sustainable saltwaterrecreational fisheries for the benefit of the nation. This year we established a new collaborative partnershipwith Bonnier Corporation—publisher of Saltwater Sportsman and Sport Fishing magazines—to promote sustainable recreational fishing. Over the past 10 years NOAA Fisheries has accomplished quite a lot with the recreational fishing community, but we know our work is not done. We will continue to support sustainable saltwater recreational fishing now and years into the future for the benefit of the nation. Which brings us to today. COVID-19 has upended life and business across the country and the world. This includes recreational anglers, for-hire operators, and the businesses that depend on them. In April and May, the agency worked quickly to allocate the CARES Act funds appropriated by the Congress and we will continue working to understand its impacts. As we collectively navigate the uncharted waters created by the COVID-19 virus, know that we do so together. This National Fishing and Boating Week, let’s all rededicate ourselves to working together and facilitating a safe return of the American public to the water and fishing. So go grab your rod! I hope to see you out on the water soon. Russ Dunn National Policy Advisor for Recreational Fisheries |

What Are Cicadas?

You may hear a humming sound when near woods this spring and early summer. What is often called locusts locally are actually cicadas and there are a variety of them. Some come out of the ground and transform into adults every year, other groups emerge every five, seven, 13 and 17 years.

The most talked about are the “17-year locusts,” a big group that comes out every 17 years in huge numbers and are named “Brood IX.” This year as many as 1.5 million adults may emerge per acre in some areas.

Female Cicadas lay their eggs on woody parts of trees and bushes. When the eggs hatch, the nymphs go into the ground and grow, eating plant roots. They grow for the years for their species, emerge from the ground, then climb up a tree or bush a few feet and come out of their shell, developing wings.

Males “sing” by rubbing membranes on their body making the sound we hear that attracts females. After they mate, the cycle starts over.

My grandfather died when I was six years old, but I vaguely remember his small farm. A tiny field was surrounded by pine trees, and whenever I visited, I would go out there and find Cicada husks clinging to the bark and collect them. Sometimes I found a one or two, other times dozens.

I have found the husks around Griffin, too. At the hunting club and on my land, if I look carefully, I can find them. The light brown husks are hard to see on the bark but they do stick out a little to help spot them.

A few years ago I was fishing Lake Sinclair and we could hear the Cicadas singing in the woods. The surface of the water was covered with dead bugs. Their bodies were reddish brown and were everywhere.

After fishing about three hours without a bite, I finally decided to “match the hatch” and tied on a red worm. I immediately started catching bass. The bass were feeding on the dead Cicadas that had died in the water and fell to the bottom and were so focused on that food source any other color did not attract them.

Carp are usually hard to catch on artificial bait, but during the Cicada hatch they come to the top and eat floating bugs. You can tie a fly that looks like the dead Cicada and catch them on a fly rod, about the only time you can do that.

This year the reason there are so many Cicadas is the 13 and 17 Cicadas cycles are matching, so both groups are coming out at the same time.

Listen for the humming sound and know that is just one of amazing parts of nature’s life cycle.

Manta Ray Conservation and Best Cobia Fishing Practices

| Manta Rays and Cobia from The Fishing Wire Cobia frequently follow giant manta rays in their migrations, and fishermen targeting the cobia sometimes accidentally hook the rays. Here’s a Q&A from NOAA Fisheries with two well-known Florida skippers on the process and on protecting the relatively rare rays. As cobia season gets underway in the Southeast U.S., NOAA Fisheries reached out to one of our best resources: our fishermen. We wanted to find out what they do or recommend to fish for cobia while protecting threatened giant manta rays. Understanding the challenges fishermen face helps NOAA biologists and fishery managers find a way to protect threatened and endangered species and still offer fishing opportunities. Captain Butch Constable and Captain Ira Laks both helped us answer the following questions. Capt. Constable has been fishing offshore in Jupiter, Florida for more than 45 years. Capt. Laks has been a charter captain and commercial fisherman out of Palm Beach, Jupiter, and the Treasure Coast for more than 30 years. Both fishermen observe individual giant manta rays along the beaches of southeast FloridaWe appreciate the input these captains provided when we asked questions about cobia fishing. What time of year do you typically see manta rays arrive along Florida’s east coast? Capt. Constable: The manta rays used to show up in March, sometimes as early as February in cold weather years, and stay through May. Manta rays would move up the coast as water warmed. However, now there are no manta rays any more off of Jupiter in the early springtime. Warmer water temps have caused a shift in species and now the giant manta rays seem to stay further north. These days no mantas seem to be found in the spring south of Hobe Sound. I discovered another large ray, the Roughtail stingray, often has cobia swimming alongside so I look for them when sight casting. Capt. Laks: Most of the sight casting for cobia from Jupiter south is done around big sharks. The challenge with that kind of fishing is keeping a hooked cobia away from the shark so that it does not get eaten. What are some of the best fishing techniques you use when fishing for cobia around manta rays? Capt. Constable: The best advice is to practice and really have good casting skills from behind and to the side of manta ray. Do not cast in front of the manta ray. That way you can make a bad cast or two and reel in and recast without spooking the fish or hooking the ray. Capt. Laks: I like to come up slowly and from behind on either side of the manta and keep as much distance as possible to make a good cast. My best approach is with the winds behind me and the angler. That allows for a longer cast and it’s less likely to spook the manta with the boat. It also allows for several attempts in order to make that perfect cast to catch the cobia and not hook the ray. Are there any specific tackle or lures you would recommend to reduce foul hooking manta rays but still are effective at catching cobia? Capt. Constable: Single hooks! No reason to fish any sort of treble hook. Safer for angler when unhooking, safer for reducing snagging the ray. It would be good if a single hook series of baits and lures came out promoting cobia fishing in a responsible way. Also, anglers should use an oversize landing net and not a gaff for most cobia. Safer for fishermen and for cobia if kept or released. Capt. Laks: I specialize in live bait fishing and use only single hooks. Treble hooks are not necessary when live bait fishing for cobia. A single hook reduces the chance of snagging a manta ray if a bad cast is made in front of the ray. If a manta ray becomes foul hooked or snagged, what can fishermen do to reduce injury and trailing line? Capt. Constable: I recommend moving the boat in front of the ray, reeling up the line and trying to pull the lure gently from that direction. The hook will often pull out of the fish and not leave the lure or trailing line. If not cut the line as close to the ray as possible. Capt. Laks: I like to position the boat and move carefully as close as possible to the manta. Then I cut the line so as to leave the minimum amount of trailing line as possible. Have you ever seen a hooked manta ray or a manta ray showing evidence of vessel interactions (e.g., prop scars or cuts)? Capt. Constable: I have seen a few lures and jigs in rays but cannot recall prop scars or major injuries. Capt. Laks: I have seen a few with larger scars but not sure the cause of those injuries. What are some best practices for safe maneuvering your vessel around manta rays? Capt. Constable: I believe approaching slowly and carefully from behind so that it allows the captain to position the boat in a safe way and not spook the ray or the fish. This gives anglers the time to set up their cast and when the fish is hooked, it will usually swim away from the ray at first. Cobia will sometimes try to return to the ray but if the boat is behind, you can often hold the fish away from the ray and land the fish safely and determine its size. Capt. Laks: Do not set up in front of the ray. I recommend staying a distance away to allow the manta to stay calm and act normally. I can then set up to fish for cobia from behind and to the side of the animal. Capt. Laks: I also wanted to remind anglers that just seeing one of these large and amazing creatures is a thrill all by itself. It is a fortunate part of an amazing day of fishing and the overall fishing experience. |

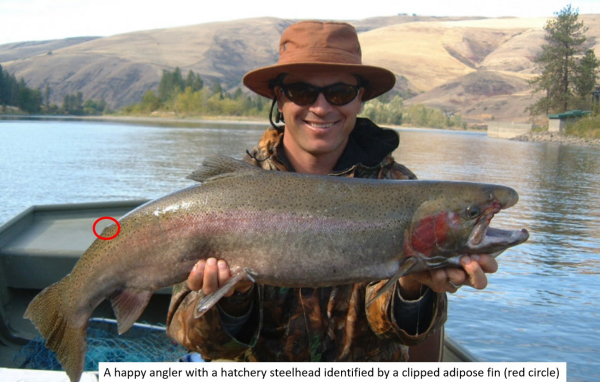

Idaho’s Fish Marking Program Has Come a Long Way

| By Braden Buttars and Joe DuPont, Idaho DFG from The Fishing Wire You set the hook and immediately your rod doubles over and there is no doubt you have hooked a big one (salmon or steelhead – you pick). Line starts peeling from your reel and you hold on for the ride. After some intense moments of thinking you may have lost the fish and some spectacular jumps, your buddy finally slips a net under the fish. After a shout for joy, what is the first thing you say? How many of you said, “Is it clipped”? I suspect many of you did seeing a clipped adipose fin distinguishes a hatchery fish from a protected wild fish telling anglers it is legal to harvest. Many of us take it for granted that hatchery fish have a clipped adipose fin, but have you ever wondered what it takes to make this happen? Joe DuPontThe Idaho fish marking program started in 1975 with a small group of people directed to tag salmon and steelhead raised in Idaho’s hatcheries. Their primary objective was to insert tiny pieces of wire, known as coded-wire tags, into the snouts of over one million salmon and steelhead. Each of these tagged fish also needed their adipose fin clipped to signify it contained a coded-wire tag. The recovery of these coded- wire tags would then help us evaluate how Idaho hatcheries contributed to fisheries in the Columbia River and ocean. Northwest Marine TechnologyIdaho’s fish-marking program has changed dramatically since 1975. In 1984 the fish-marking program was directed to remove the adipose fin from more than 9 million Idaho hatchery steelhead so that anglers could distinguish hatchery fish from wild fish. This required a small army of people equipped with scissors working 40 hours a week for about three months to accomplish this task. Once, to meet a deadline at Dworshak Hatchery in 1987, over 130 different temporaries were hired to keep four marking trailers operating 16 hours a day to remove the adipose fins from almost 3 million steelhead in 10 days. By the early 1990s, almost all hatchery Chinook Salmon released in Idaho were fin clipped, and hundreds of thousands of PIT tags were being injected into smolts to help answer specific research questions and provide managers real-time data to better manage fisheries. It got to the point that Idaho’s fish marking program could not accomplish this alone and Federal Agencies also began to help. Despite this, Idaho’s fish marking program clipped and tagged approximately 11 million juvenile salmon and steelhead each year. All this work was done by hand requiring a dedicated force of temporarily. In 2002 Idaho began to automate the fish marking program allowing more fish to be processed with less error. The first AutoFish Trailer was purchased in 2002. In 2004 Idaho purchased two additional AutoFish Trailers and two more were purchased in 2014. With this new technology, the Idaho Fish-Marking Program is now able to processes around 17 million salmon and steelhead from 9 Idaho hatcheries that contribute to major salmon and steelhead fisheries throughout Idaho and the Pacific Northwest. Now that Idaho’s fish marking program has been using automated trailers for 18 years, they have refined this process to where most fish never need to be touched by a person. To make this happen, the automated trailers are parked right next to the raceways where the fish are being raised. This allows the fish to be directly pumped from the raceway, run through the marking trailers where their adipose fins are clipped and coded-wire tags are injected, and then discharged back to a nearby raceway with no direct human contact. The first time you step into one of these marking trailer is seems more like you are entering a high tech computer facility than a place where fish are being marked. These automated trailers have the ability to sort individual fish by size using video imaging so that the right size fish goes into the right machine. This is required because each machine is programmed precisely to handle certain sized fish. Once a fish is sorted into the right machine, it gently clamps the fish in place and in a fraction of a second it can insert a coded-wire tag, clip its adipose fin, and confirm that the adipose fin was removed adequately. All this is accomplished without removing the fish from the water or using any type of anesthetic which reduces stress on the fish. For more detail on how this process click on this video link fish marking video. Roger Phillips Because of this technology, we now have an accurate count of all clipped hatchery fish at each hatchery and how these fish were marked or tagged. The application of these technologies allows fisheries managers to evaluate, track, and manage fish to provide for the protection and recovery of wild fish, while maximizing commercial and sport use of hatchery fish. In case you were wondering, in 2019, Idaho’s Fish-Marking Program was responsible for marking 16.35 million juvenile fish (10.7 million salmon and 5.65 million steelhead) as well as manually inserting 398,443 PIT tags across 9 anadromous fish hatcheries managed by the Idaho Department of Fish and Game. |